Hellfire Heroes: The Diabolic Protagonists of the Comics

In American comics, the heroes are often on the side of the angels – good people blessed by benevolent destiny with the science, magic or aptitude to fight evil. However, there is a rich comics tradition of protagonists of diabolical derivation saving the day, sometimes unintentionally (in the course of their duties to demonic masters) and sometimes intentionally (in their efforts to rebel against infernal authorities).

In American comics, the heroes are often on the side of the angels – good people blessed by benevolent destiny with the science, magic or aptitude to fight evil. However, there is a rich comics tradition of protagonists of diabolical derivation saving the day, sometimes unintentionally (in the course of their duties to demonic masters) and sometimes intentionally (in their efforts to rebel against infernal authorities).

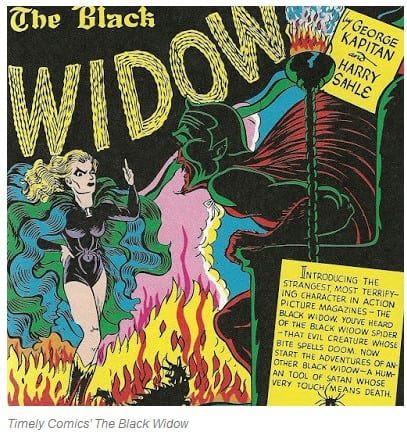

Comics protagonists with diabolic origins appeared as early as the Golden Age of Comics (circa 1938 to 1954). The first such character was the Black Widow – Claire Voyant was an attractive blonde spirit medium who, upon her death from an unjust murder, was recruited by Satan to send wicked men to Hell. Garbed in the distinctive “black widow” costume given to her by Satan, her appearance in Timely’s (later Marvel’s) Mystic Comics #4 (July 1940) gives her the distinction of being the first costumed, super-powered female character in comics. Wonder Woman would not appear until All-Star Comics #8 (December 1941), and the Amazon debuted after yet another infernally gifted protagonist appeared in the comics pages.

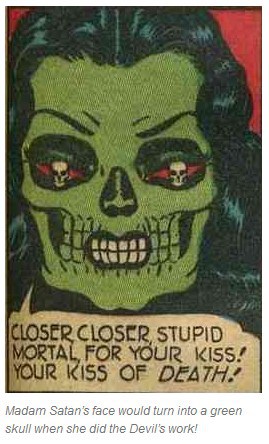

Madam Satan debuted in MLJ (later Archie) Comics’ Pep Comics #15 (May 1941). A wicked, beautiful brunette recruited by the Devil to send evil men to Hell, Madam Satan’s attractive face would turn into a horrific green skull while doing the Devil’s work. While both the Black Widow and Madam Satan had similar origins and missions, the Black Widow was a slightly more ambivalent character. Arguably she was never a villain, but a character who sought vengeance for her murder and was empowered by Hell at the price of sending evil men to their just punishment. Madam Satan, on the other hand, was a wicked woman who Satan admired for her sins. That Madam Satan went after evil men was the only morally comforting aspect of the character’s adventures.

Indeed, both female characters willingly served the Devil. Neither character ever made any effort at rebellion or escape from their diabolic pact. Both characters are attractive females that send men to their doom, and as such fit comfortably into the archetype of the femme fatale. Parents (who might object to their children reading the adventures of female protagonists that served the Devil) could perhaps take comfort knowing that the characters were illustrating the consequences of moral transgression.

Still, the social mores of 20th Century American culture made it difficult for readers to sympathize with protagonists in the service of Hell. Both characters’ strips had short runs – Black Widow’s adventures lasted 5 issues, and Madam Satan’s lasted 6 issues. Madam Satan’s strip would be replaced by a more wholesome and enduring strip, one featuring the adventures of a teenager from Riverdale named Archie Andrews.

While 1940s American cultural mores might have inhibited the popularity of protagonists of diabolic origin, the adoption of the Comics Code by comics publishers in 1954 prohibited the publication of such characters. The Comics Code, a comics industry reaction to public outcry over the perceived horror, violence, and sexual themes of comic books, required that Good must always win out over Evil in comic books. Morally ambiguous protagonists like the Black Widow and Madam Satan were unwelcome in the wholesome moral stories that comic book publishers were now required to print. Consequently, during the Silver Age of Comics (circa 1956 – 1970), there were no diabolic protagonists in American comics – with one bright red exception.

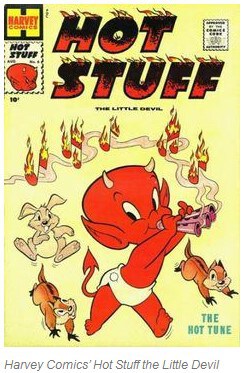

Hot Stuff the Little Devil is a good-hearted devil in a diaper. Appearing in Harvey Comics’ Hot Stuff #1 (October 1957), Hot Stuff was the most enduring of American comics’ diabolic protagonists, appearing in comics from the 1950s through the 1990s. The little red devil, with his magic pitchfork and the ability to produce fire, was funnily mischievous, regularly performing good deeds. Despite Hot Stuff’s innocent adventures, he (unlike other Harvey characters) never made the transition to other media like cartoons or movies. Also, Hot Stuff had few crossovers with other supernatural Harvey characters like Casper the Friendly Ghost or Wendy the Good Little Witch. Perhaps even a cute, harmless devil like Hot Stuff had a hard time escaping the public’s unease with demonic protagonists.

It should be noted that Marvel Comics’ Daredevil character, which appeared in 1964, has no supernatural origin. As a young man, attorney Matt Murdock was blinded by radioactive waste, but the accident heightened his other senses to superhuman levels. Murdock adopts demonic iconography (horns and, later, a crimson costume) in creating his superhero identity of “Daredevil”, but has no diabolic connection.

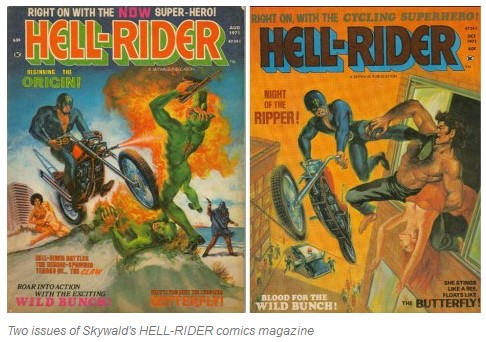

Likewise, the first hell-themed comics hero of the Bronze Age of Comics (circa 1970 to 1985), Hell-Rider, has no supernatural or diabolic origin, but his garb evoked demonic iconography. The character appeared in two issues of Skywald Publications’ black-and-white comics magazine Hell-Rider (August and October 1971); these black-and-white magazines were outside the Comic Code’s jurisdiction, allowing for edgier stories to be told.

Riding a flame-thrower-equipped motorcycle, martial artist and lawyer Brick Reese would take super-strength-inducing drug Q-47, don a skin tight blue costume (including a mask with a yellow devil’s trident on it) and bring justice to the streets of Los Angeles as Hell-Rider. While Hell-Rider’s publication run was short, he was the first hell-themed character of the Bronze Age, and his creator, Gary Friedrich, would go on to create a more iconic diabolic motorcycle hero with Ghost Rider.

In 1971, the Comics Code was relaxed to allow comic book publishers to produce horror comics. Werewolves and vampires were back, along with swamp monsters and zombies. And when DC Comics asked Jack Kirby to create a comic with a monster protagonist, Kirby created a demonic super-hero. Published in 1972, The Demon evoked Arthurian legend and demonology in telling the story of immortal protagonist Jason Blood, cursed to forever be the alter ego of the demon Etrigan as the Demon keeps the world safe from supernatural threats.

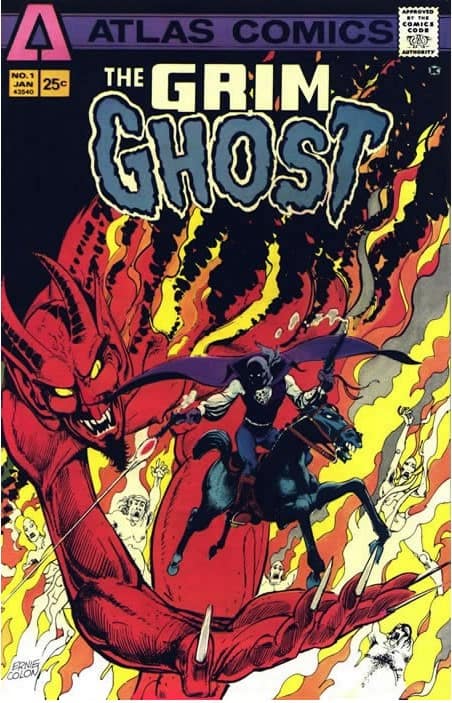

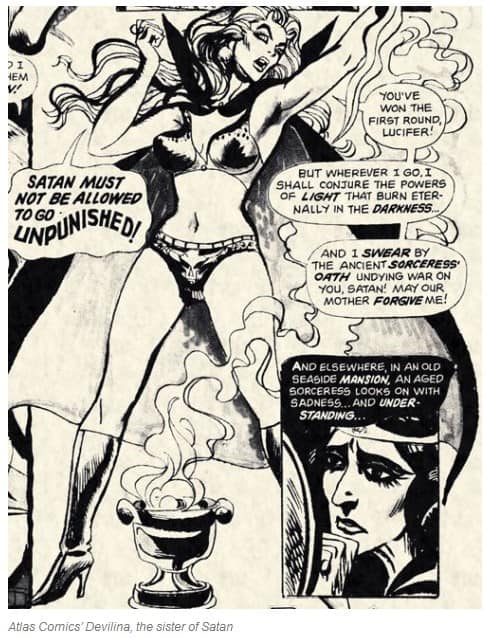

Also appearing in 1972, Marvel Comics’ Ghost Rider was motorcycle stuntman Johnny Blaze, who sold his soul to a demon in order to save (as it transpires, unsuccessfully) the life of his stepfather, and as a result transforms into the flaming-skulled, motorcycle-riding avenger the Ghost Rider. Marvel produced two sibling diabolic protagonists in the 1970s – Daimon Hellstrom, the Son of Satan, who rebels against his demonic father’s plans, and Daimon’s sister, Satana, who uses her sex appeal to destroy evil men by consuming their souls. Daimon and Satana both inspired, perhaps, the creation of Atlas Comics’ brimstone babe Devilina (the “sister of Satan”), who would star in two eponymous black-and-white magazines published in 1975, as she rebelled against her brother’s evil. In 1975, Atlas Comics also published the adventures of the Grim Ghost, a masked highwayman recruited, after his death, by the Devil to send evil-doers to Hell (in exchange for the Devil letting the highwayman avoid his just torment in Hell).

At Marvel Comics, the Gargoyle was a man who sold his soul to Hell in exchange for the prosperity of his home town; he renounces his pact and joins the super-heroic Defenders, but as a consequence of his bargain is now trapped in the form of a gargoyle. Also at Marvel, New Mutant Magik was kidnapped and taken to the dimension of Limbo; she rebels from her demonic captors and becomes a sorceress, eventually commanding the demons of Limbo. While at DC Comics, writer Paul Levitz and artist Steve Ditko’s immortal warrior Stalker fights evil forces in order to win back his bartered soul from a demon lord. Also, Raven rebels against her demon father, Trigon, and joins the Teen Titans on Earth as a superhero.

If there is a theme that connects most of the Bronze Age hell-spawned characters, it is rebellion against authority. Even the Grim Ghost, who willingly serves Hellish authority, does so to avoid a punishment decreed by higher authority. These comics protagonists were safely exploring rebellion in a context that was permissible to American culture. After all, there could be no taboo in rebelling against the commands of Hell. In a post-Watergate, post-Vietnam era, this theme of rebellion against unjust authority should have resonated with readers.

The Modern Era of Comics (circa 1985 to present) would produce its own brimstone protagonists. In 1985, in the pages of DC Comics’ The Saga of the Swamp Thing #37, writer Alan Moore and artists Steve Bissette and John Totleben introduced British working class mage John Constantine. Constantine’s ongoing supernatural adventures would see him invoking and manipulating demonic forces in order to protect the world (and himself). At one point, Constantine receives a blood transfusion from a demon; the demon blood gives him supernatural healing abilities, slows his aging, and protects him from vampire attacks.

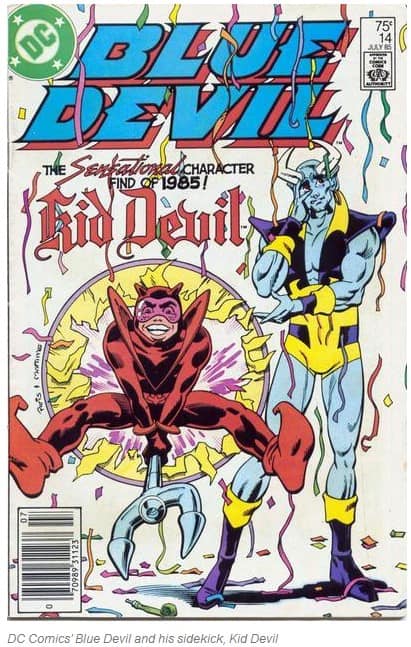

Marvel published prose horror writer Clive Barker’s creation, Saint Sinner, a character possessed by both a demon and an angel. At DC Comics, stuntman Dan Cassidy is trapped in a hi-tech Blue Devil costume when he is attacked by a demon at a film shoot. Later, both Dan and his side-kick Kid Devil would become actual, physical demons in the course of their adventures. Another DC character with infernal power is mage Sebastian Faust (son of longtime DC villain Felix Faust), whose soul was sold to Hell by his father. Garth Ennis’ Preacher series featured Jesse Custer, who is joined with the offspring of angel and demon and has the power to compel people to follow his commands.

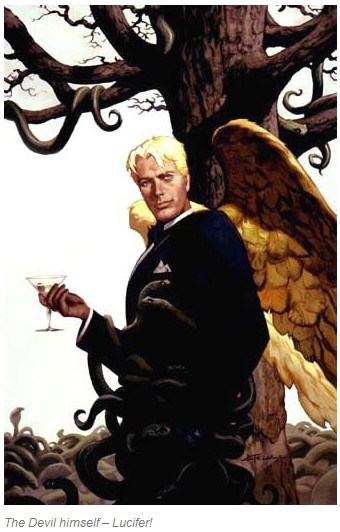

The most direct brimstone protagonist from DC Comics, however, is Lucifer. Renouncing the throne of Hell in the pages of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman series, the character would later get his own comic, which lasted for 75 issues, in which the protagonist would challenge the forces of Heaven and Hell to achieve his agenda.

[SPOILER ALERT: The last sentence of the following paragraph may spoil the ending of Mark Millar and Peter Gross’ Chosen miniseries.]

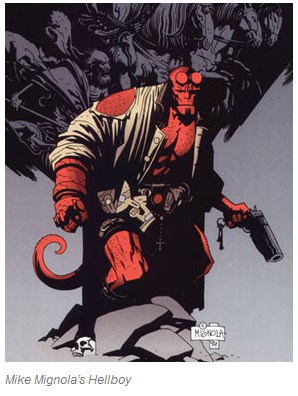

The most enduring hell-powered protagonists of the Modern Era are creator-owned characters. Todd McFarlane’s Spawn is deceased government hitman Al Simmons, who makes a deal with the devil and becomes a super-powered soldier of Hell; Spawn has been published since 1992. Mike Mignola’s Hellboy is a demon trapped on Earth and raised by humans, a true hero who fights occult menaces around the world, in adventures published since 1994. Less enduring was Jack Kirby’s Satan’s Six – six inept protagonists who unsuccessfully but humorously attempt to send souls to Hell. Also, both Mark Millar and Peter Gross’ Chosen miniseries and Garth Ennis and Jacen Burrows’ Chronicles of Wormwood depict reluctant Antichrists (Jodie Christianson and Danny Wormwood, respectively).

The brimstone protagonists of the Modern Era are united by a theme of isolation, featuring characters at odds with both Heaven and Hell, and/or separated from humanity by their appearance or background. They are great examples of the conflicted characters common in the Modern Era, dancing a fine line between the forces of Good and Evil as they struggle with their nature.