After a month or two, Simon gave Stanley a break, or maybe it would be better described as busywork – text features were needed to qualify for magazine postal rates, Simon told him to write a short Captain America story that would be accompanied by two panels of illustration. He turned in twenty-six ham-fisted paragraphs, with the title “Captain America Foils the Traitor’s Revenge,” which he signed with a pseudonym, so as not to derail his future career as a serious writer. The byline read “Stan Lee.” – Sean Howe, Marvel Comics: The Untold Story

Stan Lee’s first credited comics work was on a text piece in Captain America Comics. These text pieces were common during the 1930s and 40s, the period known as the “Golden Age of Comics”. At the time, the United States Postal Service required comic books to have at least two pages of text to be considered a magazine and qualify for the cheaper magazine postage rates.

With only two pages, writers like Lee were limited to approximately 1,500 words with which to craft their stories. Writing the text pieces must have seemed a chore to comics creators. Readers (both kids and adults) bought comic books for the comics features, not prose fiction; the text pieces were unlikely to be read, and the stories were only expected to satisfy the postal inspectors.

Although the text pieces were common in Golden Age comic books, reprint collections of Golden Age material often don’t include them. Comics scholars are primarily interested in the comics work of that period, and unfortunately don’t provide much examination of these text stories.

Looking at a few examples of text stories from Golden Age comics, the stories are often fast-paced but flimsy and predictable. To be fair, the same might be said about some of the comics featured in the comic books, but the text stories don’t have colorful, dynamic artwork to help the story along.

Below are summaries of a few text stories, including samples (in bold) of some of the prose:

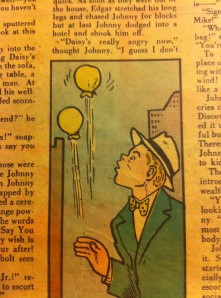

“Guarding an Heiress: A Johnny Thunder Story” (author/text illustration uncredited) (All-Star Comics #3, 1940, All-American Publications/DC Comics)

Johnny’s attention was caught by cries coming from the mannequin. Discovering it was hollow, he opened it up, and out stepped a beautiful but frightened young lady.

This text piece features comics character Johnny Thunder, able to call upon the help of a magical thunderbolt that grants his wishes for one hour when Johnny says the words “Cei U”; humorously, Johnny doesn’t know the magic words, but just happens to say the homonymic words “say you” when he’s in trouble. Johnny tries to buy a mannequin from two strangers so that he can practice saying “pretty things” to impress his aloof love interest Daisy Darling. It turns out that the strangers are crooks using the mannequin to conceal their kidnapping of a rich heiress. Johnny and his thunderbolt rescue the heiress, and Johnny is hired to be her bodyguard. Johnny and the thunderbolt foil another kidnap attempt, but a jealous Daisy gives the heiress a black eye for trying to “monkey with my boy friend”, an ending which is intended to be funny.

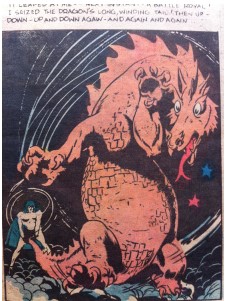

The story isn’t that bad; it’s somewhat humorous and entertaining. But keep in mind that – in this same comic book – in the comics features, Dr. Fate is projecting fire from his hands and the Spectre has a dragon by the tail.

“Murder on Water” by Joseph Greene/no text illustration (Green Lama #2, Spark Publications, 1945)

A little man was deep in the easy chair. The small table beside him was cluttered with books. The wall behind him was lined with shelves, each jammed with more volumes. The little man himself had a thin, cherubic face, a sharp nose and chin, and crows feet around his laughing eyes.

Inspector McGabe recruits Professor Sam Hoyle (the story never reveals Hoyle’s academic field of study) to help him solve the mystery of a wealthy man that was murdered in the middle of his swimming pool while sunbathing on a raft. Hoyle interviews only one suspect , the murdered man’s business partner; the partner reveals that he was once an Olympic swimmer. Hoyle looks around the pool and then concludes that the murderer is… the murdered man’s business partner/former Olympic swimmer, because who else would have the motive or swim skills.

This story was obvious and awful, but wait – we haven’t seen the last of Hoyle and McGabe…

***

“Cobwebs of Death” by Joseph Verdy/no text illustration (Green Lama #3, Spark Publications, 1945)

Hoyle and the silent McGabe also turned and stared at the doorway at their backs. There was something queer about this place. A smell of ages, of forgotten time, of lost memories. They couldn’t quite understand it, but they began to feel uneasy.

Dr. Hoyle (notice that he is a “doctor”, not “professor”, now) and Inspector McGabe visit the burned ruins of an old mill believed to be haunted, where a businessman recently died in flames. The deceased man’s business partner takes the two investigators into the mill’s cellar, where he talks at great length about the money he and his partner expected to make, and how much richer he will be now that his partner is dead. The man explains that his partner’s lamp set fire to the combustible cobwebs in the cellar, which caused the fire. Hoyle proclaims that this is impossible and orders McGabe to arrest their guide, because cobwebs don’t flare up and burn, so clearly the man soaked the place in gasoline and led his partner into the “death trap”.

This story is just as clumsy as the first Hoyle adventure, but the purple prose is entertaining.

“Peters Rings the Bell” by Joseph Verdy/text illustration uncredited (Green Lama #4, Spark Publications, 1945)

“Well, remember this, Callaghan. In my day we had wooden ships and iron men.” He jerked a gnarled thumb toward the dark river. “Nowadays we got iron ships and wooden men.”

“Old” Peters is an 82-year old former sailor bitter about not being able to get work at sea. He works as a watchman at the docks, and some Nazi agents try to force Peters to help them escape the police. Peters uses his esoteric maritime knowledge to signal the authorities, who apprehend the agents. The story is well-written and the protagonist is sympathetic, but the story’s resolution depends on an unbelievable and disappointing gimmick that is revealed to readers only at the end of the story.

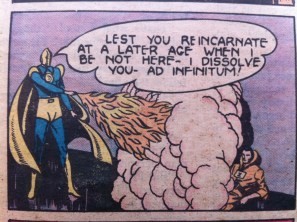

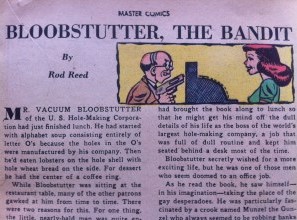

“Bloobstutter, the Bandit” by Rod Reed/text illustration uncredited (Master Comics #86, Fawcett Publications, 1947)

But it was not an ordinary broom. It was a witch’s broom. It would carry Bloobstutter anywhere he wanted to go or do anything he wanted done. All the little man had to do was make a wish in rhyme.

Mr. Vacuum Bloobstutter runs the U.S. Hole-Making Corporation, and we find him in a restaurant eating alphabet soup consisting of only the letter “O” (because his company makes the holes in them) with “hole” wheat bread. Bloobstutter is a short man who carries a witch’s broom around with him, which grants his wishes, so long as they are in rhyme. Reading a book entitled “Famous Criminals from Jesse James to Sivana” (note the reference to iconic Fawcett comics supervillain/Captain Marvel nemesis Dr. Sivana), Bloobstutter is inspired to wish that he was a criminal:

“Sometimes when I read this book I wish that I could be a crook!”

Bloobstutter’s mind is altered so that he thinks he is a criminal, but no one takes the mild-mannered company executive seriously; he accidentally gets mistaken for another criminal and runs from the police. He eventually gets caught by the authorities and wishes that that he had never been a crook. It’s a short, funny story, and well-written, if predictable.

***

The five text pieces reviewed above are not the best prose ever written, but some were mildly entertaining and all were interesting examples of the expectations of comics publishers during the Golden Age. Comics scholars would do well to examine these text stories in greater detail.

NOTE: The text stories and images from the Green Lama comics come from Dark Horse Comics’ Green Lama Featuring the Art of Mac Raboy: Volume One, which reprints the first four issues of Green Lama, including the text stories. The images from All-Star Comics #3 come from a 1975 DC Comics reprint. The images from Master Comics #86 are taken from the original comic. The images in this post are used for information purposes only, and are the property of their respective owners.