Batman’s archenemy The Joker has had various origin stories over the years, and there have also been conflicting testimonials from his creators about their inspiration for the character. But this article isn’t about any of those origin stories. This article is about how declining comic book sales, less censorship, bad business practices, and the success of a horror comic paved the way for a psychotic super-villain character to star in an eponymous ongoing comic book series in the year 1975. This article isn’t about the origin of The Joker; it’s about the origin of The Joker.

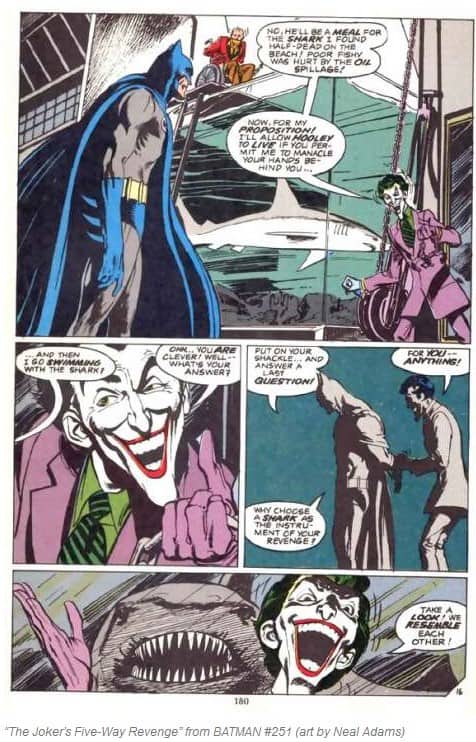

The Joker’s portrayal in comics has varied over the years; since his first appearance in 1940, the character has been a criminal mastermind, a monstrous psychopath, a camp villain, and a nihilistic terrorist. In the 1970s, Batman writer Denny O’Neil and artist Neil Adams crafted Batman stories that were true to the character’s 1940s-era detective roots; the Batman became a darker character, and so did his archenemy. In “The Joker’s Five-Way Revenge” (Batman No. 251, September 1973), O’Neil and Adams portray The Joker as an insane, murdering psychopath; O’Neil and Adam’s influential interpretation of the character made The Joker into a frightening Batman adversary.

O’Neil and Adams were able to depict a darker Batman and Joker due to changes made in 1971 to the Comics Code. The Comics Code Authority was a self-censoring review group created by comic book publishers in 1954 in response to public backlash against the perceived violent and horrific content of comic books during that period; the organization’s “Comics Code” limited the level of violence and horror that could be published in comic books. However, in 1971, several changes were made to the Comics Code that allowed for edgier material to be published; for example, comic book publishers were now able to depict drug use in comics, as well as sympathetic portrayals of criminals (so long as the villain was ultimately punished for committing crimes) and monsters like vampires and werewolves. The latter two changes to the Comics Code would be significant in the origin of The Joker.

Marvel Comics was quick to take advantage of the Comics Code revision allowing the depiction of monsters. In 1972, The Tomb of Dracula was published; the comic starred literature’s most famous vampire, Count Dracula. Although the series initially went through several writers, writer Marv Wolfman was eventually partnered with artist Gene Colan, and their creative efforts made the comic book into a horror series with a riveting villain protagonist (Dracula) and complex heroic characters that endeavored to stop Dracula (for example, the vampire slayer Blade, and detective Hannibal King, a noble vampire who refused to drink human blood and abandon his humanity). Wolfman and Colan made The Tomb of Dracula into a well-regarded comic book success. The series would have an impressive 70-issue run.

But The Tomb of Dracula was a rare success for Marvel; during the 1970s, comic book sales were down, and all comic book publishers were struggling. Publishers were selling fewer comic books at the newsstands, and, with less sales volume, were raising comic book prices to make a higher profit margin. The price increases made comic books less attractive to their target market of young readers, which contributed to the ongoing sales slump.

To generate more sales, Marvel’s president, Albert Einstein Landau, encouraged his editors to generate more comics. Marvel turned out a heavy volume of new titles like The Champions, The Invaders, The Inhumans, Marvel Presents, Marvel Chillers, Peter Parker the Spectacular Spider-Man, Giant-Size Avengers… the long list goes on. Landau may have been named after a genius, but his strategy of printing so many new titles in a period of declining sales was financially idiotic. As comics historians Gerard Jones and Will Jacobs note in their book The Comic Book Heroes: “The result of it all? Marvel was completely dominating the newsstands, selling huge quantities – and losing two million dollars a year.”

Marvel’s competitor DC Comics was forced to print more comics to compete with Marvel for newsstand sales; DC’s management did not want customers going to newsstands and not be able to find DC’s comics amid a glut of Marvel’s comic books . DC printed new titles like Plastic Man, Metal Men, Warlord, Freedom Fighters, Claw the Unconquered, Richard Dragon: Kung Fu Fighter, Stalker… the long list goes on. With both Marvel and DC rushing to create new titles, and with traditional superhero comics not selling well, it is not surprising that both companies – looking for something new that might excite readers – printed comics starring super-villains. The changes made to the Comics Code earlier in the decade made it possible for comic books to showcase villain protagonists, and the success of The Tomb of Dracula offered hope that readers would respond to such comics.

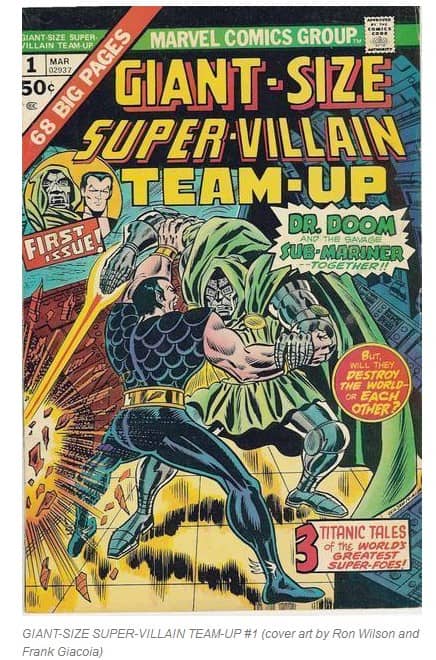

Marvel’s first super-villain-centered comic book series was Giant -Size Super-Villain Team-Up, starring Dr. Doom and The Sub-Mariner, cover dated March 1975; this series initially was published in two “giant-size” issues, but became a regular series lasting seventeen issues. (Marvel Comics’ The Sub-Mariner had been the star of his own comic in the 1940s; when the character was revived in the 1960s, he had a strip in Tales to Astonish, and later starred in his own series beginning in 1968. However, The Sub-Mariner has always been more of a noble anti-hero than villain; it is Dr. Doom’s presence – and the appearance of villains like The Red Skull in future issues – in Giant -Size Super-Villain Team-Up that makes the series a truly super-villain-centered comic).

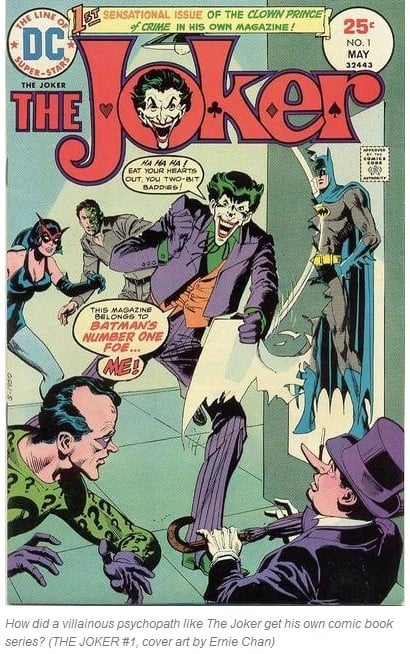

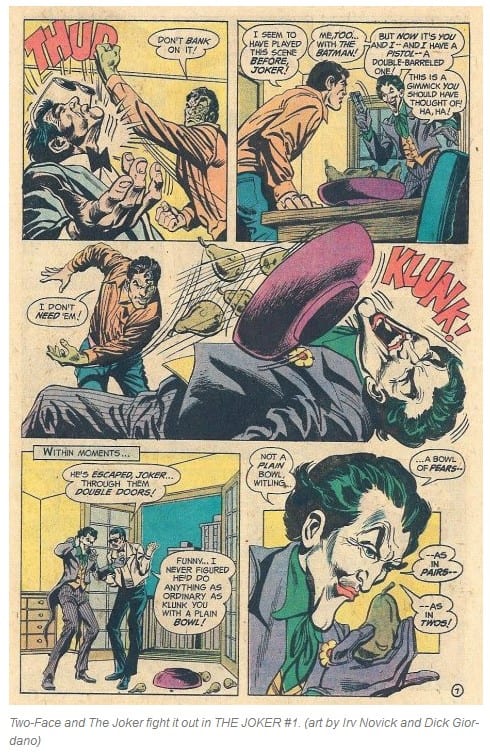

The first issue of DC’s The Joker is cover dated May 1975. This series would last nine issues, and Batman would not appear in any of them. Instead, The Joker fought various heroes (The Creeper, Green Arrow) and villains (Two-Face, The Scarecrow) in self-contained issues. Because the Comics Code mandated that the villain be punished for his crimes, each issue ended with The Joker being captured, or (in the case of issue #4) fall to his apparent death, only to return next issue with a rushed explanation as to how he survived.

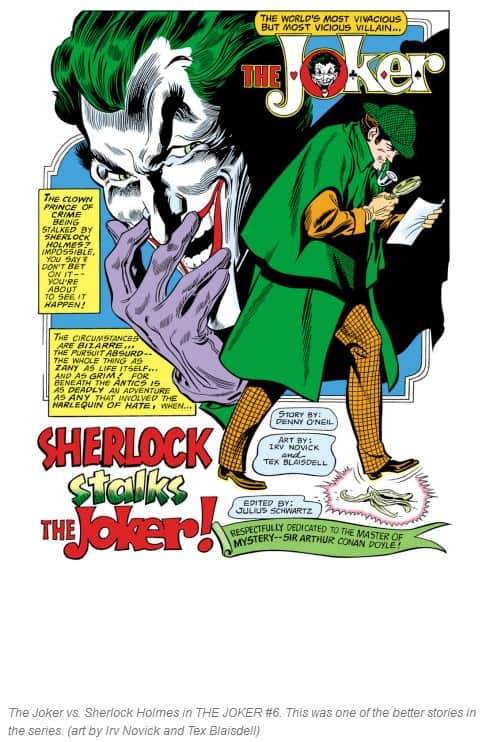

The Joker suffered from an inconsistent creative team and vision for the character. Although Irv Novick was the penciler for seven of the issues (the series’ cover artist Ernie Chan illustrated issue #3, and Jose Luis Garcia-Lopez provided art for issue #4), Denny O’Neil wrote the first three issues, Elliot S! Maggin wrote the fourth issue, Martin Pasko wrote the fifth issue, Denny O’Neil returned to write the sixth issue, and Elliot S! Maggin wrote the last three issues. The quality of stories and the death toll varied in each issue, depending on who was writing the story. When The Joker did kill someone, it was often a minor criminal henchman or a few innocent victims with whom readers did not get much opportunity to empathize.

Some of the stories were better than others. Issues #3 and #6 (both written by Denny O’Neil) are fun. In issue #3, The Joker battles the superhero The Creeper; because the hero has green hair and a maniacal laugh like the comic’s protagonist, he is mistaken for The Joker and blamed for the villain’s crimes. Issue #6 has The Joker trying to outwit Sherlock Holmes (that is, a concussed actor who thinks that he is Sherlock Holmes). While these individual stories are entertaining, the entire series is unsatisfying. The Joker is neither a frightening monster nor a sympathetic anti-hero, and the comic lacks any interesting ongoing supporting characters or surprises. The comic – so unlike the character – is disappointingly dull.

Although The Joker is not a great comic book series, its origin reveals much about the changing standards of the Comics Code and a tough period of declining comic book sales; both factors led to creative experimentation and some interesting comics. It’s too bad that The Joker wasn’t one of them.