Magic Words: The Use of Arcane Language in Weird Comics

In his essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature” (1927), author H. P. Lovecraft distinguishes weird fiction from other terror fiction, and stresses the importance of mood, or “atmosphere,” as a component of weird fiction:

“The true weird tale has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains according to rule. A certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain – a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”

Creating “a certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces” is an essential skill for writers of weird fiction, including weird comics, and one technique used to establish supernatural dread in a story is the use of arcane language. Comics creators use arcane language in a variety of ways to instill a dread of supernatural danger in readers.

In selecting an arcane language, a weird fiction author can choose an existing, not easily understood language like Latin or Aramaic, as examples, or create a fictional language. Lovecraft does both in his fiction; for example, in Lovecraft’s novella The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, the protagonist uses a Latin incantation that readers are told is “a very close analogue” to the mystic writings of French occultist Eliphas Levi. In the same chapter, the protagonist also uses a fabricated language to invoke one of Lovecraft’s fictional deities, Yog-Sothoth: “Charles was chanting again now and his mother could hear syllables that sounded like ‘Yi nash Yog Sothoth he Igeb throdag’ – ending in a ‘Yah!’ whose maniacal force mounted in an ear-splitting crescendo.”

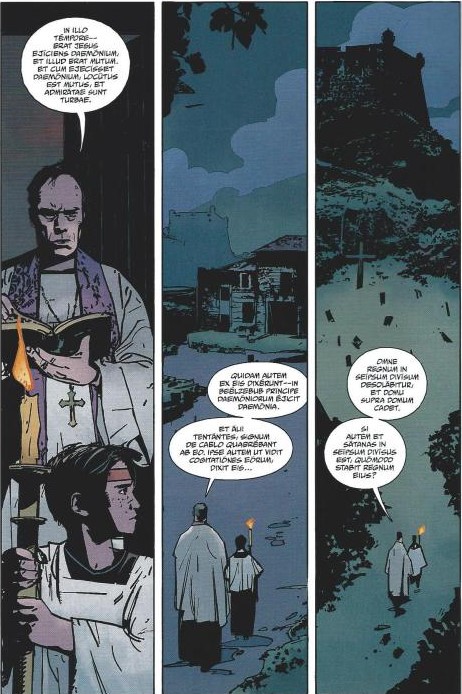

In the Dark Horse Comics series Hellboy and the B.P.R.D.: 1952, storytellers Mike Mignola and John Arcudi use both archaic and fabricated languages to create an atmosphere of supernatural dread. In the second issue, set in Brazil in 1952, the creative team depicts a Catholic priest and an altar boy walking in the dark from their church towards the graveyard near a ruined castle, while the priest recites Latin. The priest hopes to vanquish a strange monster that has plagued his town and prompted an investigation from the American Bureau of Paranormal Research and Defense (B.P.R.D.)

The use of Latin neatly establishes the mood of the comic. The Latin Biblical verses are from Luke 11:14-17, and tell the story of Jesus exorcising a demon. Although the Latin verses are appropriate for the situation and Catholic characters, the language gives even readers with no understanding of Latin a sense of the solemnity and antiquity of the pending conflict. In contrast to the B.P.R.D. agents who later engage in physical combat with the monster using modern weapons, the priest’s use of Latin identifies the conflict as an ancient, supernatural one.

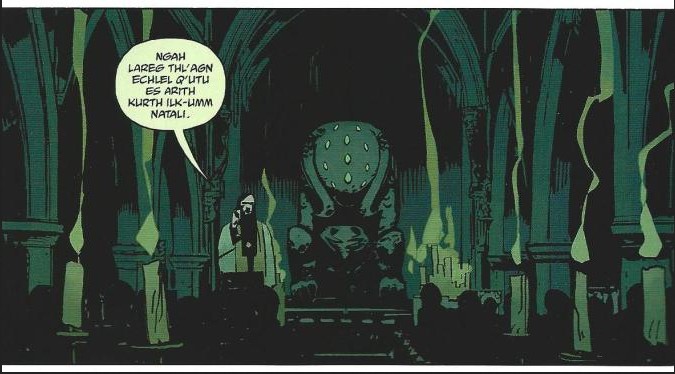

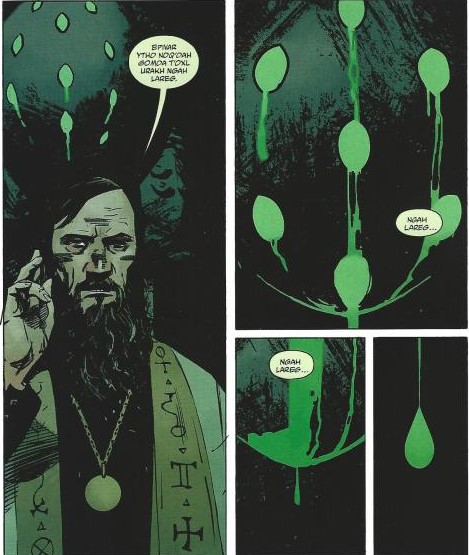

In issue three, the monster grabs a B.P.R.D. agent, giving the agent a brief vision of an occult ceremony taking place in the castle. The officiant in this vision stands before a strange statue, reciting an apparently fictitious language. Both the statue and language seem inspired by Lovecraft’s fiction, and the repetition of the strange words “NGAH LAREG” by the officiant creates an anticipation of pending otherworldly danger.

In the first issue of the Image Comics series Nameless, writer Grant Morrison also uses the repetition of arcane words to create unease. On the first page, readers learn that an astronomer has killed his family and then himself in a gruesome fashion. Above the bodies of dead children are written – evidently in blood – four strange words: “ZIROM TRIAN IPAM IPAMIS.”

On the second page, we see a deranged, bloody man being taken by police from another brutal crime scene. The man is screaming obscenities, as well as the same four words seen on the first page: “ZIROM TRIAN IPAM IPAMIS!” The use of these arcane words in two macabre scenes gives readers the sense that the gruesome crimes are connected in some unknown manner, making the crimes even more terrifying.

The strange words Morrison uses are Enochian, the language recorded in the journals of Elizabethan occultist John Dee, who claimed it was the language of angels. According to linguist Donald C. Laycock, who analyzes the Enochian language in his book The Complete Enochian Dictionary: A Dictionary of the Angelic Language as Revealed to Dr. John Dee and Edward Kelley, Morrison’s words are conjugations of the Enochian verb for “to be”: “zirom” – “were”; “trian” – “shall be”; “ipam” – “is not”; “ipamis” – “cannot be”.

It is currently unclear whether there is any narrative significance to Morrison’s choice of a conjugated Enochian verb to connect the horrific scenes in the comic. However, the words create a sinister impression, even if a reader is not familiar with their occult origin; indeed, they have a greater impact if one is unaware of their literal translation.

In the Image Comics series Fatale, creators Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips use the suggestion of a dangerous arcane language without actually using any words from the language. The Fatale series explores the archetype of the femme fatale, as the supernaturally ageless protagonist Josephine is pursued by a cult that worships Lovecraftian deities.

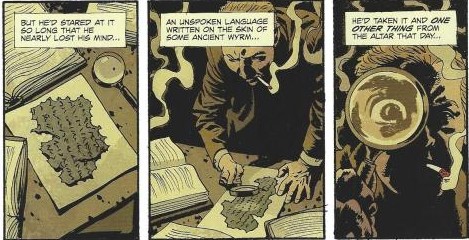

In issue five of the series, artist Phillips provides images of an indiscernible script, while writer Brubaker’s captions suggest that even looking at the strange words can cause insanity: “But he’d stared at it so long that he nearly lost his mind… An unspoken language written on the skin of some ancient wyrm…”

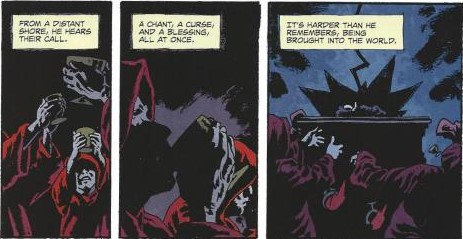

Later in the same issue, the cult resurrects their deceased supernatural leader in a ritual using an innocent baby. The cultists chant, but Brubaker does not provide any arcane words for the ritual; instead, the comic suggests the strangeness of the chant using captions: “From a distant shore, he hears their call. A chant, a curse, and a blessing all at once.”

Brubaker and Phillips use the unique visual effects of the comics medium to convey the existence of an arcane language that helps establish a creepy atmosphere for the series, without using any actual arcane words. The absence of arcane words, and the suggestion that exposure to the language might cause madness, forces readers to imagine a frightening supernatural language.

When used effectively, an arcane language can help establish the mood of a weird comic. To conclude this article, Nothing But Comics! sought the advice of award-winning fantasy author and editor Jeff VanderMeer on how a writer could best use arcane language in weird fiction. Specifically mentioning the work of Mignola and Morrison in our request for comment, VanderMeer responded:

“Well, you mention two pros of immense talent who can repurpose stuff like that and make it fresh or interesting. Otherwise, a lot of it tends to just mimic old pulp fiction and that’s a mistake, I think–depending on the context. Language that’s a little off, where a weird word or two intrudes might be a better approach. Really, every writer ought to take their arcane forbidden weird language down to the beach in the middle of summer. Then get some sunbathers to read it while children are splashing in the water nearby and everybody’s eating ice cream. If it still creeps them out, then it’s working. If everybody starts laughing and thinks it’s silly….well, you might have your answer. But, seriously—part of it has to do with how it’s embedded and how unexpected it is. And making sure it’s not the point, but in the service of something else.”