Ambush Bug’s Guide to the Multiverse

Before Grant Morrison led readers on a trip across DC’s Multiversity, before he guided Animal Man through the wastelands of Character Limbo, before DC hit the reset button of Crisis on Infinite Earths in the first place, there was Ambush Bug. In 1985, DC published a four issue mini-series starring the absurd hero of the same name co-written by Keith Giffen and Robert Loren Fleming and illustrated by Giffen. The series is a wacky, almost surreal dance through the current state of DC continuity. Along the way, Giffen and Fleming find plenty of targets for ridicule, while at the same time celebrating the silliness that is superhero comics. Does some of it get too silly? Perhaps, yet, in the same spirit of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, there is an anarchic spirit which enlivens the books, rendering nearly every page of it inspired fun.

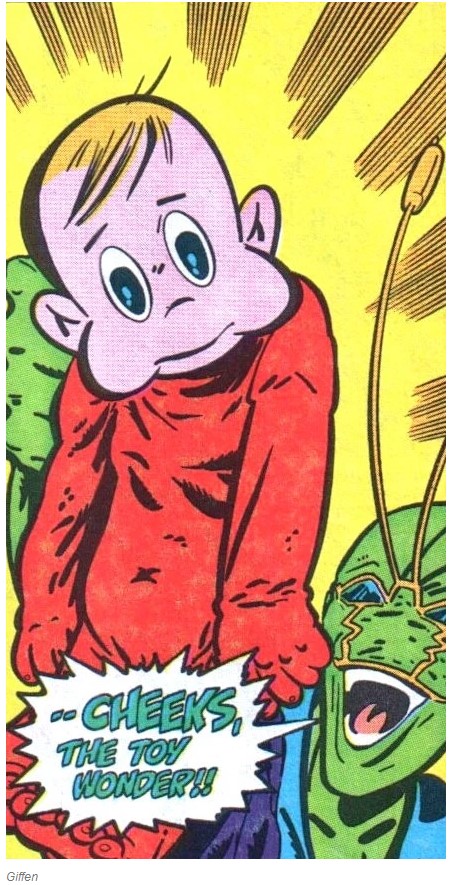

The story begins—look, best to be upfront here: plot is completely irrelevant to Ambush Bug. Yes, the first issue opens with a spaceship threatening to steal away all of the planet’s comic books. Page two reveals that this was simply a bit of tomfoolery from Ambush Bug to spike up the sales of his debut (sadly speculators are nothing new to the industry). After quickly fielding an inquiry from a prospective client (actually a wrong number trying to order a pizza), Ambush Bug adopts as his sidekick a limp doll, Cheeks, the Toy Wonder. Together they battle some disgruntled folks threatening to release the city’s store of nerve gas if those bleeding heart Democrats in Congress do not approve funding for developing more nerve gas. Ambush Bug is victorious. However, Cheeks dies heroically failing (what with his being a lifeless doll an’ all) to defuse a time bomb. Still, deaths are always good for ramping up sales, so everything works out for Ambush Bug, until he returns to his office to find Darkseid waiting for him.

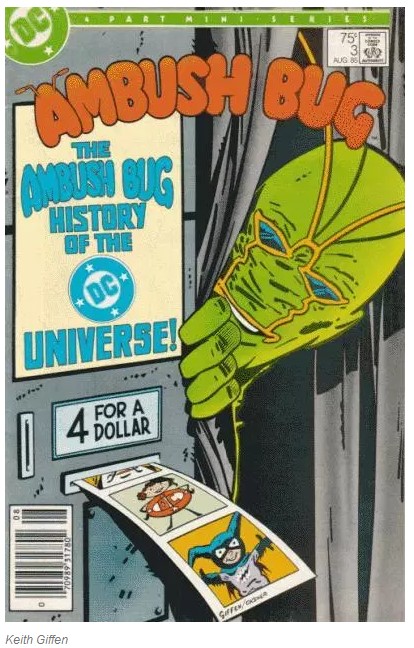

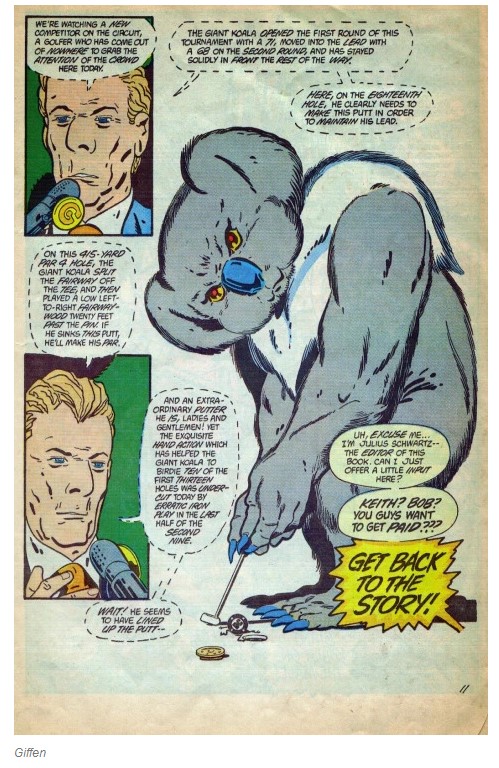

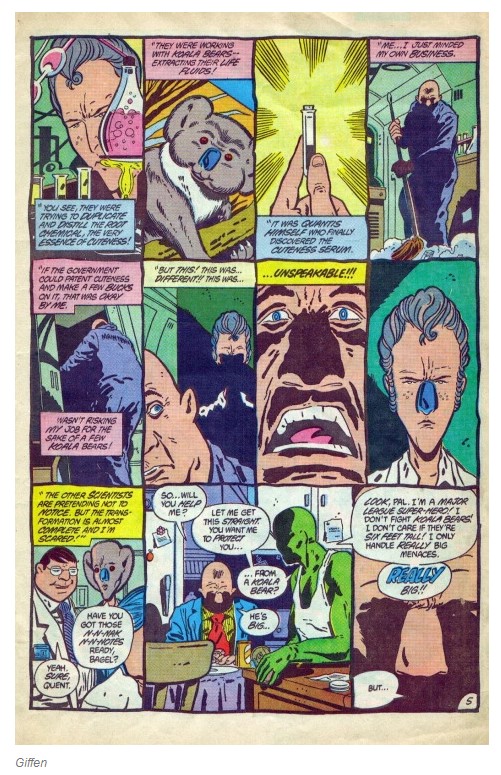

And that is about as straightforward as any installment of the series gets. As Ambush Bug progresses, the chapter grow increasingly non-linear. #1 started the trend by dropping fake ads into the flow of the narrative along with Ambush Bug’s list superhero tips (“#3 Before going to Earth-Two, check with Roy.”). #2 quickly accelerates the inanity. There is an Ambush Bug readers’ costume contest ala Patsy Walker and a Guide for Collecting Comics. Meanwhile, Giffen and Fleming gleefully smash down the fourth wall. Ambush Bug’s battle with Quantis, the Khoala Who Walks Like a Man is interpreted more than once for an image of Quantis lining up a golf put accompanied by sports broadcaster play-by-play. Soon editor Julius Schwartz (yes, that Julius Schwartz) is yelling from off page how giant khoalas do not play golf. Oh and Darkseid has infiltrated McDonalds (which come to think of it is probably as good a source for the Anti-Life Equation as anywhere).

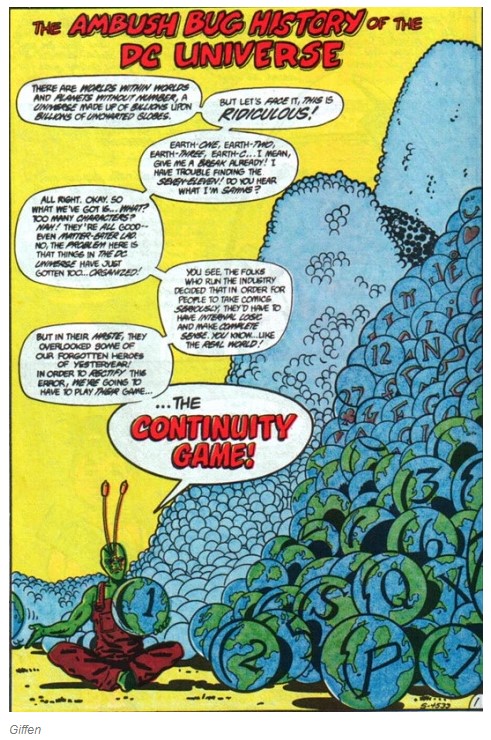

Issue #3 completely dispenses with plot, presenting itself as a guidebook for the more obscure, out of favor aspects of the DC Universe. There are odes to the bygone Legion of Superpets, Binky and Itty, among others. Giffen and Fleming are clearly taking delight in mocking some of the more outlandish moments of DC’s past, including aspects of the Bat-myths famously Schwartz exiled during his tenure as editor. The entry for Ace, the Bathound breaks down into uncontrollable laughter as the writer cannot believe how nonsensical the character’s first appearance is. Yet, none of this feels mean-spirited; indeed, there is a fair amount of affection behind the gibes. In the end, the true source of their satire is DC’s growing obsession with codifying their multiverse into something neat and orderly. Or, as Ambush Bug explains it, in order for readers to take comics “seriously, they’d have to have internal logic and make complete sense. You know . . . like in the real world!”

In 1981, Frank Miller assumed scripting duties for Daredevil, while two years later Alan Moore took over writing Swamp Thing. These two runs are often cited as representative of a sea change in comics away from four-color fantasy to the dark, gritty pain of everyday life. As with any historical benchmark, the truth is a bit more complicated, as the seeds were planted a decade earlier when the Green Goblin tossed Gwen Stacy off a bridge and Green Arrow challenged Green Lantern to discover America. (The latter was another of Schwartz’s iconic projects). Regardless, by 1985 tastes were changing and figures such as Bat-Mite were increasingly viewed as a relic of the past. After all, when during their daily life would a reader come across an imp from an alternate dimension? At the same time, Giffen and Fleming remind readers that there is such a thing as too much “authenticity.” Life is often a messy, haphazard series of events, which is why comedy of the absurd retains its appeal over the years. Sometimes the best way to understand life is to laugh along, or at, it.

Which is not to say that the work of Miller, Moore and their followers does not have merit; naturally it does. However, Giffen and Fleming’s point, represented through the character of Jonni DC, is not to obsess over it. Jonni is the “keep[er of] the continuity,” which involves tasks along the lines of correcting radio announcers when they use the Earth Two pronunciation of Mr. Mxyzptlk instead of Earth One’s. Such nitpicking takes the fun out of things. Yes, life can be quite serious at times; it can also be excitingly strange. None of it will always make sense, so why should the comic books? It is almost as if readers expect all those Darkseid teasers to actually add up to something plot-wise . . .

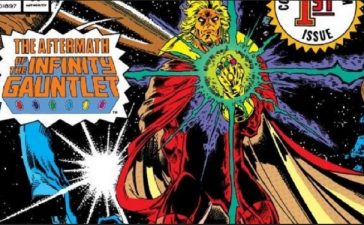

Over the course of his celebrated career, Giffen’s art has possessed a chameleonic element, spanning the clean space-age lines of Jim Starlin and the dynamic agitated flair of Jack Kirby. For Ambush Bug, he adopts a sketchy cartoonish style which matches the humorous vibe of the script. His layouts mirror the anarchic flavor of the writing, often piling themselves (and sight gags) on top of each other in a jerky manner which still maintains a sense of rhythm. The comic book may be chronicling chaos, but it is easy to follow chaos. In #3, Giffen varies his style, as necessary, for the various guidebook entries. He even gets to indulge his admiration for The King, going all out Kirby for the Darkseid cameos. In short, his lively, inventive art is the perfect fit for Ambush Bug, which only makes sense as Giffen created the character in the first place.

In the years following Crisis, Grant Morrison built a career at DC around honoring the strange, unfashionable corners of the DCU. From Animal Man’s Limbo to a Batman run based on the concept that every Batman story ever told was part of continuity to the dimensions encompassing scale of Multiversity, Morrison has pined for what came before the reboot. Ambush Bug demonstrates that this affection for the oddball existed prior to Crisis, along with a healthy sense of humor about how wacky it was. If even Julius Schwartz could join in the fun (his entry in Ambush Bug’s Guidebook is labeled “Parody of His Former Self”) then surely anyone could. It helps, from time to time, to simply have a good laugh about it all, no matter how silly.

Actually, especially when it is too silly . . .