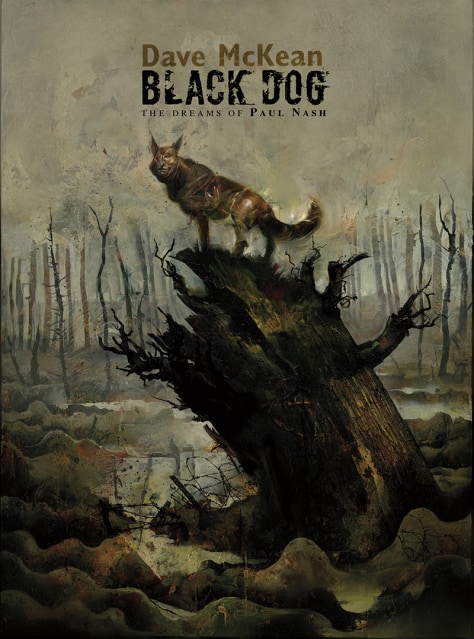

ADVANCE REVIEW OF BLACK DOG: THE DREAMS OF PAUL NASH

Dave McKean

By Dave McKean

To observe that “war is hell” is so commonplace now, it has pretty much passed into the realm of tired cliché. It does not help that its sentiment is often cited equally by doves and hawks, the latter extolling the visceral virtue of combat. Violence is a difficult subject to represent, as even the most seemingly clear-cut anti-violence message can be twisted into something laudatory (as Stanley Kubrick was repulsed to discover with A Clockwork Orange). Indeed, there is a line of thought which states that all war films, regardless of intentions, are ultimately pro-war, as it is impossible to put combat on screen without glamorizing it. (This reviewer would extend such analysis to many supposedly “moralistic” gangster movies). For his new graphic novel Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash, Dave McKean successfully avoids many of these pitfalls. He accomplishes this by almost entirely skipping the battlefield sequences, concentrating instead of the more intimate emotional toll of warfare for the fallen and survivor alike. The result is a moving mediation on the true cost of war.

Paul Nash

Paul NashPaul Nash was a British artist (1889-1946) best remembered for his work in landscapes. His work represents a shift in British depictions of the subject. Prior to Nash, British landscapes were a mostly traditional genre. Naturally there were exceptions, such as J.M.W. Turner’s proto-Impressionist brushwork ruffling the feathers of 19th Century good taste. However, Nash’s work was a more decisive break with the past, full embracing the early 20th Century movement of Modernism. His paintings abstract much of the landscape into geometric forms. The subtle gradations of hues favored by artists like Turner are replaced with flat, bold colors. Natural forms are often twisted and humans, when they appear at all, are an isolated presence. There is a whiff of the grotesque despair of Hieronymus Bosch in a few of his canvases. This pessimism is linked to Nash’s experience in World War I, a conflict which haunted his art. Nash served in the war both as solider and as an official war artist. It is this experience of warfare which is at the core of McKean’s biography.

Black Dog consists of fifteen chapter’s each depicting a moment in Nash’s life. While almost all of these are arranged chronologically, they have an episodic feel to them. McKean is less concerned with conveying the facts of Nash’s life as he is with the flavor of it. Hence, the book’s subtitle The Dreams of Paul Nash. Black Dog opens not with Nash’s earliest memory but his earliest dream. The child is confronted by a large black dog, aloof and a bit menacing. The child chases the dog which leads to Nash’s mother. “The child I was, the place, the dog, my mother, the disquiet it all expressed,” is effectively rendered by McKean’s distinctive art. The black dog gazes up at the mother, beaming in that way dogs do so often: happy just to be there. Yet the woman ignores the animal, even after a furtive lick of her hand. Then McKean pulls back the view, as the child’s perspective grows more distant, losing his baring on both this vision of his mother and the dream in general. Next McKean shows the adult Nash in military uniform, walking a rickety path above an undefined abyss. Nash relates the experience of making art to that of holding onto a dream, each new attempt another grasp at trying to retain it. Of course, it does not work, but Nash continues “panning for gold [in hope of] finding those glints of elemental truth within the noise”.

McKean’s inventive sense of design serves him well throughout the graphic novel. Scenes of the young adult Nash associating with fellow artists evokes the contemporary work of German Expressionists Otto Dix and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner whose own service on the other side of no man’s land would scar them just as deeply. At the same time, McKean’s retains enough of his own personality that the visual allusions never feel like lazy copying. This is partly done through contrasting styles, for example in the portrayal of Nash’s wedding. The service itself is shown in a manner suggestive of the illustrations of the day. Naturalism is ignored in the favor of caricature. The emphasis is not on beauty, yet there remains a gleeful charm to some of the figures along with Nash’s references to “ladies of questionable virtue, filling out the aisles” or “Margaret [his bride] kissed the boys and made them cry.” Turn the page though and the festivities grow more ominous. The couple steal away to the roof where the scene changes remarkably. The loose cartoonish style is replaced by a sprawling nighttime view of London. The medium is now McKean’s signature choice of paint and montage. A huge creature blending a fish with a blimp dominates the oppressively dark sky. Three searchlights prop “the monster aloft.” The bride and groom stand with their back to the reader, dwarfed by the Leviathan which has brought the war to the heart of the nation. McKean captures all the horrific awe of the moment with a chilling image that pure naturalism could never match.

In such a way, McKean honors Nash’s work without ever reproducing his paintings within Black Dog. At first this may seem to be a counter-intuitive decision. However, it turns out to be the right one. Despite their thematic overlays, Nash and McKean have very different styles. Nash’s work might have clashed within a McKean frame. So, McKean does the next best thing by evoking the spirit of Nash’s art, especially how it is haunted by experience on the front.

As Black Dog progresses, Nash is increasingly preoccupied by the conflict’s lingering scars. One way this is presented is through his jealousy of the free of spirit, such as a friend from school or a fellow veteran whose trauma was entirely repressed by amnesia. In each case, Nash’s attempt to find some peace in the present moment is interrupted by a sudden surge from the past. The discussion with the amnesiac Claud brings to mind memories of Billy, a young soldier felled by a sniper soon after requesting Nash’s help in composing a letter home to his parents. As for Claud, he fell ill at the age of 31, most likely a long-term victim of the poison gas frequently used during World War I. The war claims all, sooner or later. It is simply a matter of time.

Nash himself lucked into a few more years than Claud, dying at 57 from heart failure related to asthma. McKean portrays Nash as increasingly distant in his later years, suggesting that in addition to what was then termed “shell shock”, he also inherited his mother’s mental illness. (This is stunningly illustrated in a sequence of small panels, resembling a film strip, emphasizing Nash’s disconnect from his surroundings). The older Nash is, more and more he is consumed by his nightmares. However, there are flashes of hope as well. Even towards the end, Nash is still able to imagine a lush green world, where tranquility allows the leisure to paint a bathing beauty instead the mangled victims of war. Still, he cannot live in such a fantasy world and is forced to cover the beauty’s eyes with a brushstroke of paint. And yet the gleam of her gaze remains, buried, obscured, but not entirely forgotten.

Through such brilliant mixtures of text and image, Dave McKean brings to life the inner world of Paul Nash. In the process, he celebrates his art while also providing a powerful reminder of the true cost of war beyond the initial causality numbers. It is a lesson that sadly remains as poignant and necessary today as it was a hundred years ago when Nash and his comrades fought The Great War which was supposed to end all wars.

Cheers

Black Dog: The Dreams of Paul Nash will be released by Dark Horse Comics on Wednesday, October 5th.

Disclosure: Publisher Dark Horse Comics provided a review copy of this comic to Nothing But Comics without any payment between the site and publisher or agreement on the review’s content.