What does Batman mean to me? That seems like a fitting question to ask at the beginning of our month-long celebration of Batman’s 75th Anniversary. Naturally, there are many different ways that I could answer this question. Like so many pop cultural figures, Batman has been able to remain a fixture by adapting and reflecting the various eras he has lived through. It is probably not a coincidence that Editor Julius Schwartz was able to fashion his “New Look” Batman, free of camp, at the same time the overall mood of the country was darkening. So, perhaps it is most fitting if I answer “What does Batman mean to me” by returning to specific story I read at a specific age.

(And, yes, this will involve Cosmo dating himself—you have been warned).

In 1988, DC released Batman: The Killing Joke by Alan Moore and Brian Bolland. Originally intended as a one-shot, out-of-continuity tale, the book was a huge critical and popular success (my much-thumbed, slightly yellowing copy is a fifth printing). The story delves into the possible origins and motivations for the Joker, as well as the twisted bond which ties him and Batman so closely together. It also includes the (in)famous scene of the Joker shooting Barbara Gordon, leaving the former Batgirl paralyzed for the next two decades.

I stumbled upon this story somewhere around the time the first Tim Burton movie was released. Whether I bought it before or after seeing the film, I can’t remember anymore, but the two are linked in my mind. I still recall a promo magazine for the movie, in which Burton explained that Killing Joke was the first comic he ever read that made sense. (Apparently when he was a kid, he would never know what order to read the panels in, which is probably one of the truest confessions about how his mind works, for both good and bad, I’ve ever seen). So, let’s simply say it is 1989, and my early teen self is wondering through this small nook of a comic book store in a local mall. Glancing over the stacks I see the most recent printing. In a glass display case they have a first printing for much, much more. “Hmmm,” thinks younger me, “this might be worth having. Plus, hey, it’s the Joker.” So, I buy it, take it home and am simply wowed.

It should be noted that I read The Killing Joke before I read any of Frank Miller’s iconic works from earlier in the decade, so this was my introduction to a more psychological take on the character. In fact, it was the first comic I ever bought with a “Suggested for Mature Readers” label. So, in many ways, this story was my initial glimpse of not only what Batman stories could be, but what comics in general could aspire to be. Also, Brian Bolland’s art is, was, and will ever be some of the greatest to grace a tale of The Caped Crusader.

Thus, The Killing Joke made an impression on me at a young age; what it also did was stay with me as I grew older. It is one of the paramount stories I return to in my mind when I consider the essence of who Batman is. If someone asks me for a single recommendation of where to start, this is where I point them. This is because Alan Moore has crafted a story which speaks not only to the plight of spandex heroes, but to the human condition in general.

(Spoiler alert for those who have not read Killing Joke).

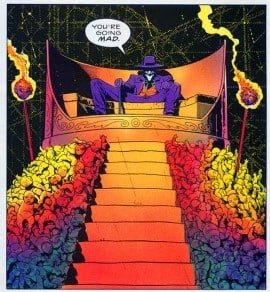

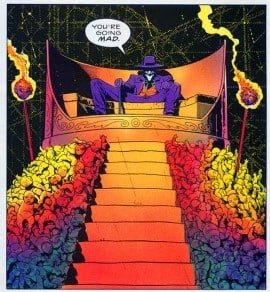

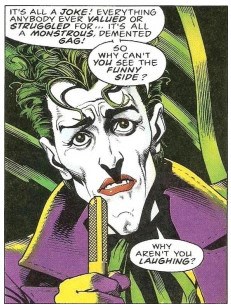

The Joker, as he sometimes does, has a plan, a method behind his madness. He does not maim Barbara out of revenge, or for the sheer thrill of the act. No, his response to her “why” is simple: “To prove a point.” Her father James is hauled away to an abandoned amusement park. There he is stripped, prodded by “freaks”, and forced to view photos of his naked daughter bleeding out from a fresh gunshot wound. All the while, he is taunted by the Joker, who only wants one thing: for Gordon to snap. The Joker has a theory: there is nothing wrong with him. He is just like anyone else. He had a hard day once, everything went bad, something flipped inside him, and all of a sudden the world made sense. He’s the same one. He’s the one who sees past the phony shells of delusion we build to trick ourselves into thinking that it all makes sense. Such worthless effort. None of it will ever make sense. Life is one arbitrary event after another. Today you lose your job, tomorrow your pregnant wife dies in an electrical mishap. Maybe the next day your parents are gun-downed in an alley, or a madman cripples your daughter before your own eyes. What difference does it make? C’est la vie; life goes on.

Or as Moore and Bolland so memorably rendered it:

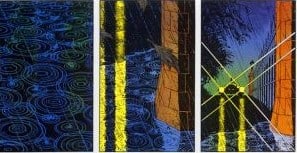

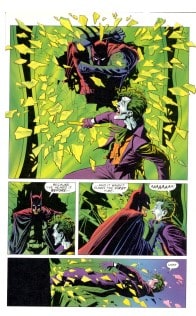

To which, Batman makes his equally iconic rebuttal:

Bruce Wayne knows firsthand what tragedy means, what it is like to have your conception of the world torn apart repeatedly. (At the time, the events of Death in the Family were not yet a year old). Bruce has as much of an excuse, if not more, than the Joker to check out of reality. He doesn’t, though, and this is what makes him the stronger man. Yes, life may by random, there may be no rhyme or reason to why one person gets cancer or another wins the lottery. We may not control what happens to us, but we decide how we respond to the situation. We may rise above misfortune, learning from it to become a better person. In essence, this is the difference between Batman and the Joker.

In the end, Moore is not simply telling a Joker story but The Joker Story. The narrative follows a pattern long familiar to readers: Joker escapes, commits some dastardly deed, is captured by Batman and returns to prison. Moore’s script reuses dialogue, most prominently Batman’s reflections on his bound relationship to the Joker. Bolland picks up on this motif in his art, as well. The first two and final two panels are nearly identical, as if you could flip back to the beginning and repeat the tale like some perpetual Mobius Strip. There have been those that have argued that Batman kills the Joker at the end of Moore’s story, but I think that this undercuts what Moore is doing. Each character is bound to the other so that neither can exist without the other. They define each other. They are modern-day mythic characters and their struggle can have no ending. It simply resets itself.

Finally, I shall invoke the “make your own continuity rule.” My Batman does not kill. (Yes, he did in the beginning; I’ll be addressing that in another post). Despite all his torments, Gordon does not snap, reminding Batman that the Joker needs to be brought in “by the book . . . We have to show him that our way works.” Good people can exist in this world without stooping to the level of animals. We can aspire higher. At the end of the day, it is our choice how we wish to live.

And that is what Batman means to me.