Well, as is frequent with summer events, a deadline was missed. I’ll just fess up now and admit that it was mine. I don’t have a penciler or a trio of inkers to blame either. My final Bat-Month article was supposed to appear last week, however, planning a wedding can take a chunk out of your time, plus that whole day job thing, and, you see, here we are. At least, I’m only a week late, which is more than can be said for a certain other event which wrapped up recently.

In my last column, I discussed a sampling of Batman and Detective Comics from the early 90s. This week, I would like to turn my attention to a third Bat-title of the period: Legends of the Dark Knight. When Legends was launched in 1989, it was the first new solo Batman book since Batman debuted in 1940. Yes, Batman was featured prominently in World’s Finest or The Outsiders, but in these series he shared the stage and/or appeared irregularly. Legends would put the spotlight squarely on The Dark Knight. In fact, a mere one panel cameo appearance by Dick Grayson would set off passionate debate amongst fans whether or not even Robin should appear in the series.

What set Legends apart from the other two Bat-series was that Legends was not set in the contemporary day. In theory stories could take place in any era, including the future; in practice, creators tended to focus on the early Year One period of The Caped Crusader. Hence the controversy over Robin. The other element, which made Legends unconventional was that each story arc would be a self-contained tale told by a different creative team. While this approach is more common these days, at the time it was pretty daring. DC could have filled this book with second-stringers or flavors of the month and it probably would have still sold well. Instead, here are some of the names which appeared in the credits of the first two years: Dennis O’Neil (three times), Mike S. Barr, Grant Morrison, Klaus Janson, Matt Wagner (on writing & art duties), Howard Chaykin, Gil Kane and Bart Sears. Clearly, DC did not skimp on the talent. Naturally, as with most anthology series, some stories were stronger than others. Today I would like to discuss one of these tales, which I recently reread, and enjoyed just as much as when it was first released.

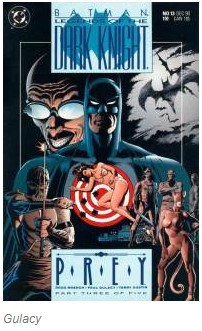

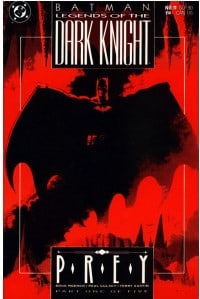

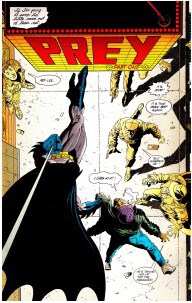

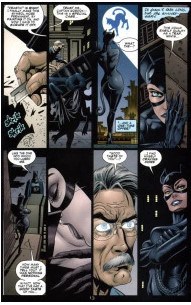

Prey, running from issues #11-5, was the third arc of the new series. Written by Doug Moench with pencils by Paul Gulacy, it depicts a young Batman still struggling to gain his footing in Gotham City. Most significantly he has not earned the trust of the city’s government or police force, beyond a familiar Captain James Gordon. Moench picks up where Frank Miller’s Year One left Batman and Gordon, doing an excellent job of fleshing out this initial stage of their relationship. Both men understand that they are vital to each other and that their campaign against crime cannot succeed alone. For example, in Moench’s telling, it was Gordon who first thought to lay a bit of cloth over a police spotlight creating the Bat-Signal. In a similar vein, Moench brings back the Catwoman from Year One. She plays only a small part in this narrative, however, it is still an intriguing glimpse into her and Batman’s budding, frustrated chemistry.

Instead of Catwoman, the primary antagonist of the story is Dr. Hugo Strange. A couple weeks ago, I discussed Strange’s earliest appearances in which he was a Moriarty-esque crime lord with hints of a mad scientist tossed in for good measure. For Strange’s first post-Crisis appearance in Prey, Moench drew on a Steve Englehart story from the 70s. Here the former criminal overlord was transformed into a medical doctor running a shady clinic for the affluent. When Bruce Wayne checks in to recover from Batman related injuries, Strange discovers the playboy’s secret. Moench takes this kernel of an idea and shapes a detailed portrait of genius driven mad by obsession. In Prey, Strange is a prominent psychologist who is brought in by the mayor to consult with an anti-vigilante (i.e. anti-Batman) police task force. Strange is fixated with Batman, fascinated and repulsed at the same time. Strange understands what drives Batman, the freedom the mask gives him, the cathartic release of violence. Strange can only imagine the pleasure it brings the vigilante. Yet, because Strange can merely dream of being it himself, he is filled with hatred for it.

In Moench’s hands, Strange is a fascinating individual, who, on the one hand is brilliant enough to deduce Batman’s identity (none of the “tracing back spare parts invoices” shortcut which Ra’s employed). On the other hand, he is deeply disturbed. Any slight from someone else is perceived as a gross character flaw on their part. He is also sadistic, a character trait he shares with his Golden Age version. Not satisfied with defeating Batman, he must see him broken, filling Wayne Manor with mannequins dressed as Bruce’s parents, playing tape-recorded messages voicing disapproval. It is a chilling scene which I remembered well even after all these years.

On art duties, Gulacy turns in some fabulous pages. His action scenes are clear and dramatic. Not surprising given his experience drawing Shang-chi, he emphasizes the martial arts elements of Batman’s fighting style. In addition, he does a great job of keeping the story flowing through the dialogue sections. This is very much a psychological study and Gulacy never lets discussions of pathology bog down the pacing. Indeed, Strange has a creepy quality, stalking his high rise apartment, delighting in the sound of his own voice. The fact that these recitations are delivered either to a mannequin dressed in lingerie or, later, the mayor’s kidnapped daughter bound to his bed, only makes the sequences more disturbing.

Almost a decade later, Moench and Gulacy reteamed for Terror, a sequel which ran from Legends #137-41. While not as strong as Prey, primarily on account of spelling out way too much motivation for the characters, it is still an enjoyable read. (DC has collected both Prey and Terror together in one trade edition). Catwoman is given a larger role, which is a plus. One memorable moment features her lured out of hiding by an impromptu Cat-Signal. This time around, Scarecrow is added to the mix. Overall, Gulacy’s art is more slack (perhaps the change in inker served him poorly), but his rendition of Scarecrow, eyes sunk back beneath his mask, is striking.

Terror is also worth reading for a scene of Bruce by his parents’ gravesite. Here he renews his pledge “to find some purpose in purposeless death, to make sense out of senseless loss.” He speaks of his limitations, his desire to do more. Bruce returns to the Manor with new instructions for Alfred. From this point on, Batman will fight crime at night, while during daylight hours Bruce Wayne battles its root causes through the charitable work of the Wayne Foundation. It is true some minds, such as Strange’s, are mad beyond redemption. It is for them that Gotham truly requires its Dark Knight. However, what of the purse snatcher living in poverty, thieving because he sees no other livelihood? Here is a battle which Bruce Wayne can fight; here is another way in which he can honor his parents’ memory. It is an affecting scene which, harkens back to the theory of Batman put forth in my first Bat-Month article: Batman is who he is because he resists the easy way out. He does not accept that sense cannot be made from the senseless turns of fate. He learns and improves, rising above circumstances to be a better person. It is the most important example that Bruce learned from his parents, and, in turn, it is the most valuable lesson the Batman continues to teach us.