As with most fans who started reading comics around or after 1986, my primary reference for Howard the Duck was the film adaptation. Not that I have seen the movie, since its (abysmal) reputation definitely precedes it. All I needed was one glance at some terrible design work to accept the general opinion that it was one of the worst films ever made. With this bias in mind, I barely gave Howard a second thought.

Flash forward a couple decades. Not long after returning to regular comics reading, I discovered Steve Gerber’s Omega the Unknown. Co-created with Mary Skrenes and Jim Mooney, Omega focused on a strange bond between a powerful alien being and a 12-year-old boy, James-Michael. Gerber would later explain that his goal was to have a teen protagonist who wasn’t a sidekick, but his own person, facing “real problems? At the same time, James-Michael had to contend with some very comic book-esque situations, such as discovering that his parents were robots. The resulting mix of offbeat fantastical with down-to-earth mundane was certainly distinct, but probably also a bit ahead of its time. Launched in 1976, Omega was abruptly canceled after ten issues due to poor sales. (Issue 10’s dangling cliffhanger, along with other assorted loose ends, were eventually tied up in rather underwhelming style by Steve Grant in the pages of The Defenders).

Not long after I had finished Omega, I was talking with a good friend of mine about it. Knowing that I wanted to read more Gerber, he handed me his copy of the Howard the Duck Essentials trade. I looked at it, and raised an eyebrow. He replied, “No trust me, forget the movie, this is brilliant. Plus, as he had just upgraded to the Howard Omnibus, I could simply keep the Essentials trade. So I took it home, stuck it on my shelf, where it remained, despite the best of intentions, unread for several years. Finally, nine days ago, I was inspired to crack it open. I was hooked by the end of the first issue.

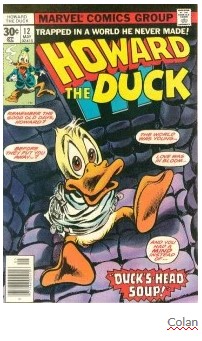

Howard the Duck first appeared in the horror anthology home of Man–Thing, Adventure into Fear (or simply Fear) #19, 1973. From the very start, this co-creation of Gerber and artist Val Mayerik, was unconventional. The first page in the collection shows Howard sitting in a swamp, smoking a cigar and refusing to progress any further in the story. He protests how he has been treated by “Gerber, Mayerik and Marvel Comics, somehow plopping him down on “your stupid earth where “I’m supposed to bare my soul . . . I refuse. This prompts a brief dialogue (in play script, no pictures), between Howard and a Voice from on High, in which VFOH tricks Howard into sticking with the narrative a little while longer, which allows for his first proper appearance, strolling out of nowhere and into a meeting between Man-Thing and Korrek the Barbarian. It may be the most arbitrary debut for a major character ever.

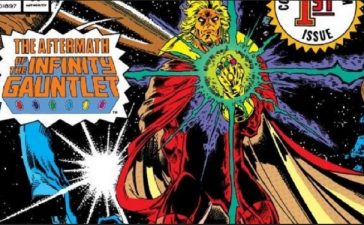

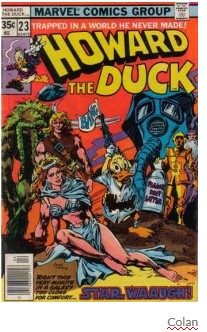

Clearly from the get-go, Howard the Duck’s story was going to be different. How different? Well, among the various obstacles tossed in Howard’s path by Mr. Gerber are a vampire cow, a deadly space turnip, Pro-Rota the mad financial wizard, a psychiatric hospital director who bears a strong resemblance to a certain former führer, a religious cult led by one Joon Moon Yuc, a fanatical organization of suicide bombers targeting cultural “indecency (led, it is implied, by a very real culture wars crusader), Dr. Angst Master of Mundane Mysticism (plus minions), and Howard’s archenemy Dr. Bong. In addition, Howard runs for President on the All-Night Party ticket (his press conference is priceless). He becomes adept at Quack Fu. In “Star Waaugh (#23), he employs The Farce to defeat the Imperium Emporium which threatens to destroy the universe through conspicuous consumption. There are also literary allusions galore (the best being the affectionate ribbing of Gothic tales in #6, “The Secret House of Forbidden Cookies).

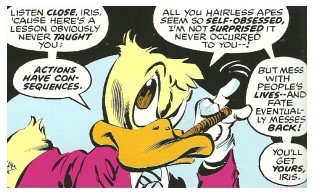

As can be gleamed from this summery, Howard the Duck is very much a product of a specific moment in cultural history, yet, at the same time remains universal. Even without knowledge of a particular reference point (and there are one or two which got by me), the stories themselves are always engaging. Part of this is the spirit of fun that is built into many of them. This is satire that had me laughing out loud on various occasions. Gerber was not simply a smart writer, but a talented one as well, able to cobble together narratives (often on an issue-to-issue basis), that never failed to keep me excited. I devoured all 32 issues of this collection as rapidly as possible. One reason for this is that Gerber surrounds with Howard with a great supporting cast. For most of the run, his main companion is one Beverly Switzler. Howard and Bev have a delightful chemistry, playing off each other quite well. (They also share in a scene in bed that the Comics Code required Marvel to edit). She is both the hairless ape who understands Howard the best, as well as the only one who can really call him out on his more anti-social behavior. Along the way this pair is joined by other characters who keep the reader interested in the ongoing arc of the narrative.

At the same time, though, Gerber clearly has more on his mind than merely parodying popular culture; like all truly great satirists, he has something about human nature to say as well. For example, Howard is chosen as best suited to wield The Farce because of his temperament, specifically his wiseass nature. His ability to “yok it up in the face of death is a greater survival skill the brawn or brains. After all, a knack for laughing at life is a primal coping mechanism. Without our sense of humor, we might very well go mad at the absurdity of it all.

Which, unfortunately, is what does happen to Howard at one point. After having traveled to our Northern Neighbor in order to battle Le Beaver, Howard breaks down from exhaustion. The following issue (#10) is given over entirely to Howard’s delusional dreams. Glancing back at his life, he struggles with concepts of social expectations and indoctrination. Where do such concepts come from anyway? Is there any law (even as basic as gravity) which can be taken for granted? Just what is the meaning of it all? This issue, like the majority of Gerber’s run, is fabulously illustrated by the legendary Gene Colan, whose imagination is more than equal to that of Gerber’s.

Ultimately, Howard’s dilemma is no different from what any of us have been forced to face at some point in our lives. True, we may not ever have to face down a literal cookie monster or team up with the 70s era Defenders, but the details are incidental. The trigger for Howard’s breakdown was should he have run away from his fight with Le Beaver? Does he owe anything to these hairless apes, or is it every duck for himself? If the universe is cruel, should we not be cruel back? One of the endearing aspects of Howard is that despite all his misanthropic wise-cracks, he still comes out fighting for the better cause. Being a dispassionate loner may sound appealing at times, yet, in the end, it is the company of others, and yes compassion for them, which keeps us sane.

And this is only scratching the surface. Gerber’s nuanced take on concerns about violence in the media is particularly good. I have not even touched upon the most famous issue of the series, “Zen and the Art of Comic Book Writing (#16), in which Gerber abandons sequential narrative altogether. In its place, he critically analyzes himself and his writing. Similar, if less extreme, meta-devices are scattered throughout the run, going all the way back to Howard’s earliest appearance in Fear #19. (If Grant Morrison is not sending royalty checks to the Gerber Estate, he really should be). Even more than Omega, this is a comic that was ahead of its time. We should be lucky that it lasted almost three times as long as Omega. Still, similar to Omega, the plug was pulled too early. By 1978, Gerber had gotten into a dispute with Marvel over the ownership/licensing rights for Howard, which ultimately cost him his job at the publisher. (Incidentally this is also the reason Steve Grant, not Gerber himself, wrote the final wrap-up for Omega). Howard the Duck lasted four more issues with three different writers: Marv Wolfman, Mark Evanier (co-scripting with Gerber on a final contractually obligated story), and Bill Mantlo who was brought in to resolve the dangling Dr. Bong/Bev plotline. I have not read these issues, as the Essentials collection stops with Gerber’s departure (#27). They have a poor reputation, though I find it hard to believe that collection of talent could have bungled it that badly. Perhaps, Howard is one of those characters whose voice only his creator can get right? Still, they’re probably worth a read; I mean, who wouldn’t want to read something entitled “The Final Bong!

Regardless, the years passed and Howard slipped out of fans’ attention. Then his movie tanked and along with it Marvel’s interest in reviving the character. Eventually Gerber would turn in a mini-series for the character, which is now on my to-read list, along with some Man-Thing, and that Nevada series which spun out of Neil Gaiman’s fondness for #16. Oh and maybe I’ll finally look at that final Dr. Fate series Gerber was writing when he passed away. That same friend who gave me the Howard trade has always said how much he liked it . . .