Review of Sandman Overture #6

Two years ago, Vertigo launched Sandman Overture, a prequel to Neil Gaiman’s much beloved Sandman series. Gaiman’s return to The Dreaming was a true event. His script sparkled; his characters were as vivid and lively as they were two decades ago. Williams’ art was stunning. Fans, both new and old, were enchanted. Then, Overture encountered a couple delays and a narrative which was supposed to unfold over a year took twice as long. However, the quality remained strong, especially over the previous two installments. Issue #6 brings Overture to close in a fitting manner. In short, it is a masterful achievement.

The plot of Overture has followed Dream as he has searched out a threat to the entire fabric of the cosmos. It was made doubly personal first by killing off one of his aspects, and secondly by being his fault for occurring. Ages prior he had spared the life of a dream vortex. This seeming act of compassion, in truth a manifestation of his arrogance, left behind a festering, wounded black star which was now consuming all existence. At its heart, Sandman was about Dream’s emotional growth, his gradual transitioned into a more empathetic being. Part of this process was facing the consequences of his past mistakes, which had a nasty habit of returning to bite him. Overture lays the groundwork for this journey by depicting the initial chinks in Dream’s armor of self-regard. Readers had always assumed that Dream’s broadening was the direct result of his decades of captivity; Overture reveals that the process had already begun.

For most of Overture, Dream has been reacting to events around him, his only proactive actions being to gather information about the situation. In #6, Dream unveils his plan for saving existence. It is a risky, long-shot endeavor which requires much from him while also relying on others to do their part. “It is as easy as changing one’s mind, as difficult as moving a galaxy . . .” (OK, if Death were here she would probably roll her eyes and observe that for some it takes less effort to move a galaxy than to change their mind).

Dream’s plan goes to the very heart of his nature: reality is defined by dreams in the same way that dreams define reality. After all, how can I say something is “dreamlike” if there is no understanding of “realism” against which to contrast it? There can be no surreal without a concept of what is real, or vice versa. Dream’s plan goes even deeper though; he wishes to realize the concept that dreams can literally reshape reality. Calling back to the story “Dream of a Thousand Cats,” Dream persuades 1000 myriad beings to dream away the vortex, imaging a past where he fulfilled his duty by killing it when he should have. As I said, the simplest of plans, as well as the least predictable.

“Dream of a Thousand Cats” is not the only shout-out to other tales. Gaiman expertly references future events without it ever feeling like obvious fan service. Indeed, the whole narrative has a natural, organic rhythm to it. All the threads come together brilliantly, resolving the plot of Overture while seamlessly flowing into the first pages of Sandman #1. Gaiman stated that Overture would explain how Dream was so weakened that he could be easily confined by a coven of gentlemen mages and Gaiman succeeds at that task. There is a huge emotional punch as fans watch Dream step unknowingly into the next chapter of his life.

The issue does not end there, though, but adds an epilogue. Here a familiar face appears to air a long held sibling grievance. It is another skillful example of drawing on past and future events simultaneously. It also lends a wistful air to the final pages.

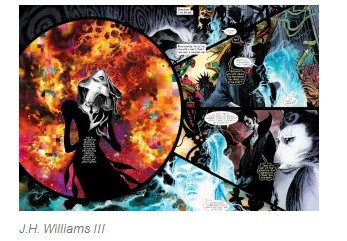

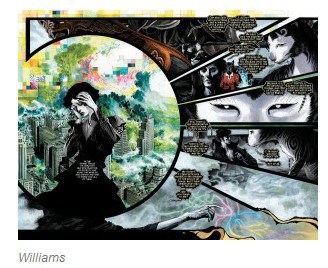

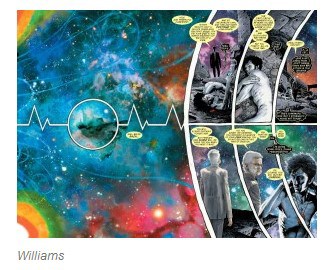

All of this is beautifully illustrated by J.H. Williams III. Gaiman has worked with a wide variety of talented artists over the course of Sandman’s history, and Williams fits well into that tradition of collaboration. Overture is arguably the most cosmic of all the Sandman tales, and Williams’ art rises to the occasion. The issue consists mainly of two-page spreads, any of which could be singled out as a masterpiece. All sense of traditional page layout has disappeared as square panels give way to images which often bleed from one space into another. Backgrounds are filled with all manner of details. Williams’ figural work is impressive as well. The weeping figure of Death, the penetrating stare of Dream Cat, the spent haggard Dream all stay long in the memory.

Then for the epilogue, Williams shifts his style. He switches over to single page compositions which maintain all the boldness of the epic two-pagers. The epilogue is about the shifting sands of memory, a sensation which Williams conjures powerfully. He is assisted by the always great colorist Dave Stewart, who applies sepia tones to this section as ably as he brought out the otherworldly in the main section. Together they create some truly striking art. Williams has long been a singular talent, but with this project he raises the bar for himself even higher.

All together Overture #6 was a powerful experience. Sandman has been an important part of my life for over two decades; its characters are as familiar as some people I know. I shall admit that I was originally a little nervous about the prospect of Overture. Were my expectations set too high? Could lightning strike once again? I am happy to report that it has. Very much so. #6 is a highly satisfying ending for a worthy addition to the Sandman mythos.