Among his various editorial decisions at Marvel, I am guessing that Stan Lee does not keep on his résumé: “Guy Who Turned down Star Wars.” Yet that was what he did when Lucasfilm publicist Charles Lippincott came knocking on Lee’s office door. Now, true, it was 1975 and the project was still in development. Lee’s quite reasonable, request was come back when you have an actual movie to show me. So Lippincott did, and Lee would have said no again, if it was not for the intervention of editor/writer Roy Thomas. Thomas was interested in the property and wished to edit it himself. Lee (who I can easily imagine shrugging his shoulders or making some similarly dismissive gesture) agreed.

Among his various editorial decisions at Marvel, I am guessing that Stan Lee does not keep on his résumé: “Guy Who Turned down Star Wars.” Yet that was what he did when Lucasfilm publicist Charles Lippincott came knocking on Lee’s office door. Now, true, it was 1975 and the project was still in development. Lee’s quite reasonable, request was come back when you have an actual movie to show me. So Lippincott did, and Lee would have said no again, if it was not for the intervention of editor/writer Roy Thomas. Thomas was interested in the property and wished to edit it himself. Lee (who I can easily imagine shrugging his shoulders or making some similarly dismissive gesture) agreed.

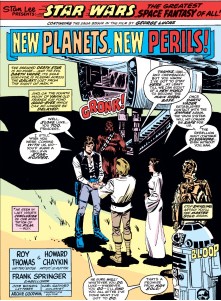

Lucasfilm was eager for Star Wars to have as many avenues to its core fanboy audience as possible, so they allowed Marvel to have the license with no royalty obligations (unless it sold 100,000 copies, which I doubt anyone in the room believed would happen). Thus in 1977, Marvel released a new science-fiction series, written/edited by Thomas and illustrated by Howard Chaykin, adapted from the George Lucas film we now know as Episode IV: A New Hope. Back then it was simply Star Wars, and it sold a lot of copies. According to Editor-in-Chief Jim Shooter, the title was so successful, it saved the publisher from a dangerous financial state (even after Lucasfilm returned to renegotiate those royalty fees post-100,000 units sold).

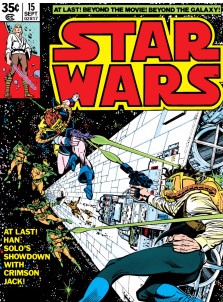

Thomas and Chaykin spent six issues adapting the movie, after which they were left a best-selling title and no source material. Thus, they had to start devising their own. They were allowed use of all the main protagonists: Luke, Leia, Han, Chewbacca & the pair of bickering droids. According to i09.com, Lucasfilm did require that any delving into the Luke/Leia dynamic was off the table. Also unavailable was Darth Vader (though this did not prevent his occasional cameo through flashback or dream sequence). These restrictions, however, were also freeing for Thomas and Archie Goodwin who succeeded Thomas as writer/editor. Whatever temptation there might have been to rehash some of the main plot threads of the films would have been made quite difficult by Lucasfilm, who also had to sign off on every script prior to production. Thomas and Goodwin had no choice but to send their heroes into fresh scenarios full of new characters.

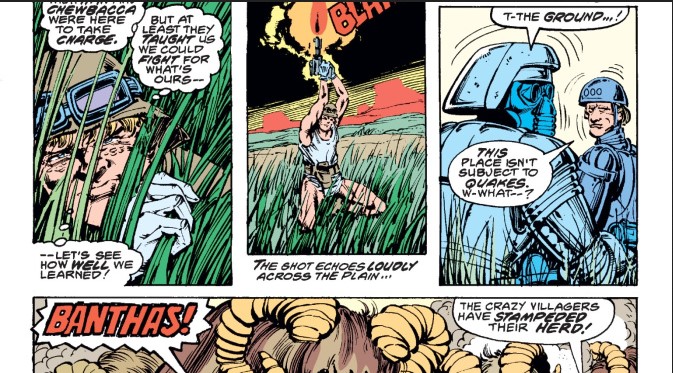

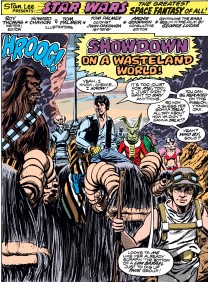

Recently I read a run of these early adventures. Full disclosure: I skipped the six-issue New Hope adaptation and went straight for the new material in #7, making my way through #20. Thomas begins the post-movie material with a clever nod to the past. He strands Han and Chewbacca on a remote, desolate planet. In a local canteen, Han is approached by a trio of desperate farmers seeking hired guns to relieve them from Cloud-Riders who annually raid their community. Han agrees and soon assembles a ragtag bunch of fighters to the cause. If this sounds like The Magnificent Seven, well yes. In the past, I have touched on the thematic overlap between the Western and sci-fi genres, which are apt in this story.

However, it should be remembered that The Magnificent Seven was itself a remake of the Japanese masterpiece Seven Samurai by Akira Kurosawa. (There is a rich back-and-forth of influence between samurai and Western movies, but that is a subject for another day). George Lucas has long been on record about the debt he owes Kurosawa (though I really wish Lucas would find a better method of repayment than some of his embarrassing attempts at Asian-esque names). From a plot standpoint, the main precursor is The Hidden Fortress with its narrative of an experienced samurai trying to sneak a headstrong princess out of enemy territory while accompanied by two bickering peasants. However, stylistically, he borrowed from many of Kurosawa’s films. Probably the most distinctive technique would be his use of the wipe-cut, which is rarely seen outside of the work of either filmmaker.

While this homage to the past is intriguing, Thomas is smart enough not to be a slave to it. Unlike The Magnificent Seven, not all the characters have clear analogues to the originals. Thomas spins his own story, while sprinkling in some allusions of his own, such as a clever nod to Don Quixote. In the end, the borrowings are merely a framework for building an entertaining adventure full of engaging characters. This is a story that not only introduces an anthropomorphic, meat-eating green-furred rabbit named Jaxxon, but makes the reader want to see more of him.

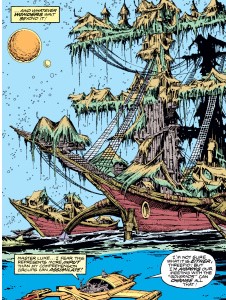

Thomas only co-plotted the last installment of this storyline, giving scripting duty to Don Glut (whose diverse career included writing for superhero television cartoons, contributing to Masters of the Universe character creation and directing films like The Erotic Rites of Countess Dracula). Beginning with #11, Goodwin took over the title where he remained into the late 40s. He followed Thomas’ example of exposing the characters to new worlds and creatures. One notable aspect of these stories is that most of them were extended arcs; one-and-dones were rare. This allowed Thomas and Goodwin to settle into a scenario and really engage in some strong world building. Goodwin is particularly good at this, first on a waterworld full of sea dragons, then on The Wheel, a huge space Vegas.

One of the advantages that Marvel had in the 70s, as opposed to 2015, was that the universe of Star Wars was still a pretty blank slate. There were no handbooks on planetary systems or a Wikipedia pages dedicated to Creatures of Star Wars. Naturally, alien forms from the film do appear (the Marvel Bullpen seemed to be particularly fond of Banthas), but there is a lot of new design going on as well. In addition, the absence of Vader allows for the crafting of new adversaries for the Rebels, including an Imperial Commander trying to manipulate the profits of The Wheel into Imperial, i.e. his, coffers. Actually, for much of the issues I sampled, the Empire is not even a presence. All of this creativity is illustrated by a series of all-star artists which includes Chaykin, Carmine Infantino & Walter Simonson. Simonson’s contribution is particularly strong, and is the among the best Star Wars art any comic publisher has released.

Marvel would continue publishing Star Wars comics until 1987, putting out adaptations of both Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi along the way. Dark Horse Comics would take over the license in the early 90s and hold onto it until Disney purchased Lucasfilm. Last week, Marvel released its first Star Wars comic book in nearly thirty years. In my review, I expressed some disappointment that writer Jason Aaron was sticking too closely to the formula of the source material. When I made the observation, I was thinking specifically of these earlier Star Wars narratives. They are full of the sense of adventure and character that fans remember from the first film, yet also avoid the pitfalls of simply depicting a variation of that story.

While many Star Wars tales have been told since Marvel’s first series debuted in 1977, the universe is a large sprawling place, full of still-unexplored corners. My hope is that as Marvel’s new Star Wars line continues to develop, they will take more cues from what they published back in the 70s. I am not saying we need the return of Don-Wan Kihotay or Jolli the space-pirate, though I would not complain if they popped up, especially Jolli; her story deserved a much better ending than the one Goodwin gave her.