Invading Canada: We Stand on Guard and the History of U.S./Canadian Conflicts

Co-created by writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Steve Skroce, the Image Comics series We Stand on Guard imagines the U.S. military’s invasion of Canada one hundred years in the future. The premise of the science fiction comic may seem shocking or absurd; Canada and the United States are strong allies and the possibility of the two nations ever going to war seems unlikely. However, there is a history of military conflicts between the two countries, and in the 20th Century both Canada and the United States developed secret plans to invade the other.

In preparation for this week’s debut of We Stand on Guard, Nothing But Comics reviews the history of military conflicts between the United States and Canada.

The Invasion of Canada – 1775

During the American Revolution, the Continental Army invaded the province of Quebec in the hopes of persuading French-speaking Canadians to join the Thirteen Colonies’ revolution against the British. Two American military expeditions – one led by General Richard Montgomery and the other by Colonel Benedict Arnold – invaded Quebec. Although Montgomery’s expedition captured Montreal, the American forces were weakened by expired enlistments, smallpox, and a lack of supplies. Montgomery was killed during the attack on Quebec City, and Arnold led the remaining American forces until they were driven back from Quebec City and eventually out of Canada by the British. The American failure to capture Quebec City and the Continental Army’s poor administration of Montreal did not inspire French-speaking Canadians to join the Revolution, and the invasion was unsuccessful.

The War of 1812

During America’s war with Great Britain in 1812, the United States saw an opportunity to seize Canadian territory and initiated a three-pronged attack against the British colony. U.S. military forces led by Revolutionary War veteran and hero General William Hull left from Detroit to capture Canada’s Fort Malden. The British recruited Native American allies to fight the U.S. military, and Hull retreated back to Detroit after his supplies were captured by Native Americans led by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh. Intimidated by the Native Americans and British cannonball fire, Hull surrendered his forces and Detroit to the British without a fight. The U.S. military later court-martialed Hull, who was convicted of cowardice and neglect of duty.

The other prongs of the Canadian invasion did not go well. America’s failed effort to capture Canada’s Queenston Heights on the Niagara River resulted in the capture of 950 Americans, with approximately 100 Americans killed in the battle. And the American soldiers commanded by General Henry Dearborn – tasked with capturing Montreal – retreated from the border after a few skirmishes without ever reaching Canadian territory.

“The Pork and Beans War” – 1839

The 1783 Treaty of Versailles ended the Revolutionary War, but was vague about the boundary between the State of Maine (originally a district of the State of Massachusetts) and Britain’s Canadian province of New Brunswick. The matter came to a head in 1839 over timber rights, when Maine authorized its militia to arrest Canadian lumberjacks cutting down trees in the disputed territory near the Aroostook River. The lumberjacks armed themselves and captured the American militia at night, holding them as prisoners in the New Brunswick town of Woodstock.

Tensions escalated, with Maine sending more militiamen to the Aroostook region and the U.S. Congress authorizing the creation of a military force led by General Winfield Scott to defend the region. In Canada, the British military and New Brunswick militiamen increased their presence near the disputed territory. However, the territorial dispute was settled diplomatically by the Webster-Ashburton Treaty of 1842.

There were no combat fatalities, and the dispute is remembered as the “Aroostook War” or the “Pork and Beans War” (some believe this name comes from the supposed favorite meal of lumberjacks, while others believe the name refers to the rations of the British troops dispatched to the disputed area.)

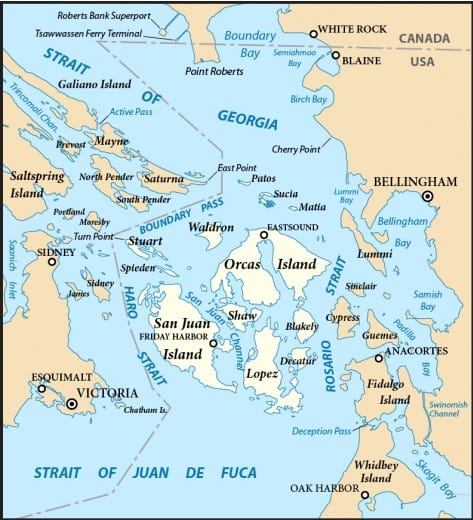

“The Pig War” – 1859

In 1859, a border dispute regarding the ownership of the San Juan Islands near Seattle and Canada’s Vancouver Island erupted when American farmer Lyman Cutlar killed a pig that was eating his potatoes. The pig belonged to a neighbor, who was a British citizen. British authorities threatened to arrest Cutlar, and American forces under the command of Captain George Pickett were dispatched to protect him. The British sent warships and marines to the islands, and Admiral Robert Baynes had orders from Vancouver’s colonial governor to engage the American forces. Baynes, however, refused, believing it was foolish for Britain and the United State to go to war over a pig.

The matter was settled diplomatically, with both the United States and Great Britain having joint occupation of San Juan Island until the question of ownership could be settled by arbitration. In 1872, the arbitration commission declared that the islands belonged to the United States.

The only casualty in the conflict was the pig.

The Fenian Raids – 1860s

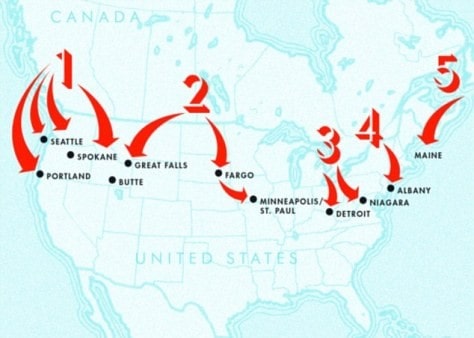

Founded in the United States in 1858 by Irish Americans, the Fenian Brotherhood organization supported Ireland’s independence from Great Britain. The Fenians came up with the idea of conquering Canada in the hope of ransoming it back to Britain in exchange for Ireland’s independence, and in the summer of 1866 launched a five-pronged attack on Canada.

U.S. officials were aware of the Fenians’ intentions but – remembering Britain’s sympathies towards the Confederacy in the recent Civil War and aware of the political power of Irish American voters – did nothing to stop them or warn the British. Most of the 1866 raids were unsuccessful, although the Fenians were victorious in the city of Ridgeway, Ontario; however, the Fenians quickly retreated to America as British and Canadian forces prepared to counter-attack.

The Fenian raids on Canada continued sporadically until the early 1870s, when President Ulysses S. Grant made it clear that the United States would no longer ignore attacks on Canada from American territory. The last Fenian raid – on the province of Manitoba in 1871 – concluded when the U.S. Army arrested the Fenians involved in the raid.

Defence Scheme No. 1 – 1920s

In 1921, amid tensions between America and Great Britain over Britain’s unpaid $22 billion World War I war debt to the United States, Canadian colonel James “Buster” Brown devised “Defence Scheme No. 1.” The plan – intended to be used should Canada ever learn of America’s intention to attack the British dominion – called for an invasion of the United States to destroy America’s infrastructure and slow down U.S. military forces until aid could arrive from Great Britain.

Oddly, Brown and his subordinates gathered intelligence for the plan by travelling undercover as civilians to sites along the U.S./Canadian border, and noted in their findings that the men of Vermont were “fat and lazy” and that rural American women were “heavy and not a very comely lot.”

In 1928, the head of the Canadian Army, General Andrew McNaughton, dismissed the plan and ordered all copies of it destroyed.

War Plan Red – 1930s

In the 1930s, the U.S. military planned for a hypothetical war against Great Britain. This plan – code-named “War Plan Red” – outlined an invasion of Canada in order to weaken Britain and prevent Canadian resources from being used against the United States.

Famed American aviator Charles Lindbergh contributed ideas for the plan by recommending potential bombing targets and even suggested the use of chemical weapons, which were prohibited by the Geneva Convention. American military planners anticipated that the captured Canadian territories would be kept after the war and annexed by the United States.

In 1935, the United States Congress appropriated funds for the construction of three secret military air bases near the Canadian border that would be used to attack Canada if needed.

War Plan Red was one of many contingency plans against potential American enemies (including Germany and Japan), and with the outbreak of World War II the war plan was considered unnecessary and abandoned. The plan was declassified in 1974.

***

Although We Stand on Guard is a science fiction comic, its premise of a military conflict between the United States and Canada has historical precedents. The current good relations between the United States and Canada have not always existed, and the creative team behind We Stand on Guard makes us ponder whether the United States and Canada will ever again be military antagonists.