Graphic Policy’s Brett Schenker Discusses the Airboy Transgender Controversy

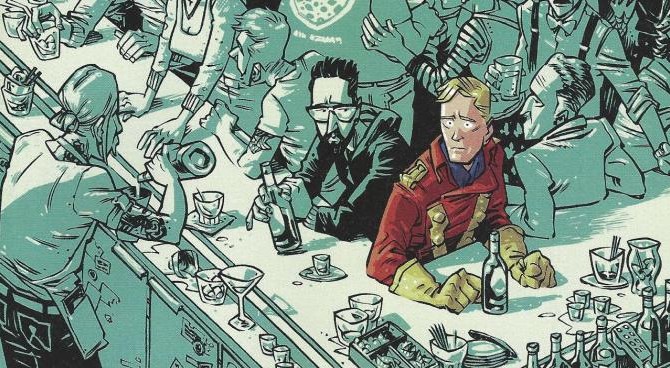

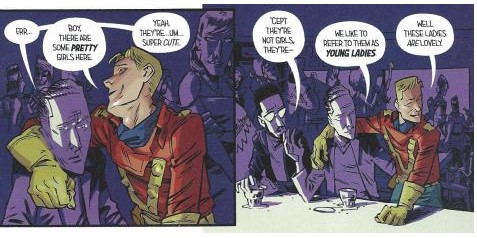

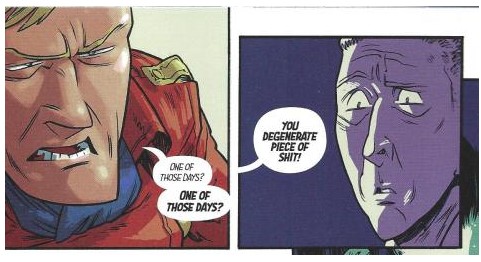

During last week’s Image Expo event, comics blog Graphic Policy initiated a Twitter campaign asking publisher Image Comics to pull copies of Airboy #2 from shelves. Written by James Robinson and illustrated by Greg Hinkle, the Airboy series presents boorish fictional versions of the creative team as they attempt to craft – amid a haze of booze and drugs – a reboot of the Golden Age comics hero Airboy; in the first issue, the fictional Robinson and Hinkle are surprised by the appearance of the Airboy character in the “real” world. Airboy #2 depicts Airboy and Robinson receiving oral sex from transgender women; Airboy is unaware that these women are transgender, and as Graphic Policy notes, “A debate ensues about the ‘men’ they hooked-up with, Airboy storming off complaining about the ‘degenerate’ world.”

Several sites, such as The Rainbow Hub and Comicosity, criticized the comic’s narrative for being transmisogynistic and transphobic, and the issue prompted Graphic Policy to launch its Twitter campaign; in response, Robinson issued an apology via GLAAD, stating that he had “inadvertently hurt and demeaned a community that the real non-fictionalized version of myself truly respects and admires.”

Curious about how Graphic Policy came to its decision to launch the Twitter campaign, Nothing But Comics contacted Graphic Policy’s founder and “Blogger in Chief” Brett Schenker to learn more.

On July 2nd, Graphic Policy initiated a Twitter campaign during the Image Comics Expo, asking Image Comics to pull Airboy #2 from shelves based on the perception that the comic was transphobic. Could you tell us how Graphic Policy came to the decision to initiate the Twitter campaign?

First, thanks for reaching out. Yes, the Twitter campaign launched on July 2nd, but what folks overlook was we were trying to have a dialogue for over 36 hours at that point, a dialogue that was one-sided up until we launched the campaign. Our initial post on the topic was at 11:19pm ET on June 30, a few minutes after our friends at The Rainbow Hub launched their post.

I, and my podcast cohost Elana, come from the world of politics and activism. We used our political geek friends and our connections to help boost this. Elana particularly reached out to contacts of hers at GLAAD who eventually spoke out.

If an opportunity arises to raise the profile of an issue, especially after it was ignored as this was, you take it. That opportunity was Image Expo which we knew they would be using a hashtag to promote things. We reached out to others we worked with, to see what they thought of the action, and what the specific ask should be. We felt that it should be transgender individuals, not us, who determine what the “ask” in that campaign was. We timed the action to launch as Image Expo took off, taking a page out of Activism 101. It wasn’t until others screamed “censorship” that people started to really pay attention.

Graphic Policy called for Image Comics to pull Airboy #2 from shelves. Had that suggestion been followed, it would have denied readers access to the comic. Some might argue that the suggestion was a form of censorship. How do you respond to the perception that the Twitter campaign was advocating censorship? Also, why did Graphic Policy feel that calling for the comics removal from shelves was the right course of action or strategy to address its perception of the comic’s transphobia?

Actually, you’re falling for the individuals conflating censorship, banning, and pulling something. Banning usually involves an act of government. We did not address the government, so that’s not the correct term. Censoring is actual deletion or prevention of an idea or feeling. We never asked for the deletion of the comic at all.

Those that have draped themselves in the 1st Amendment are deflecting from an actual discussion of the material, something we had been trying to do for 36 hours at that point, but they also need to reread the 1st Amendment. The 1st Amendment says “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” I’d love to be an elected official, but last time I checked I wasn’t, and there was no legislation being lobbied for. I’m not even going into the fact that speech is limited according to the courts (free speech is a myth we tell ourselves), or the fact we all self-censor as part of the societal compact we abide by. To me, those claiming all of that, or artistic freedom, are just deflecting from the issue at hand.

Pulling is a completely different thing. It is asking the petitioned to engage in speech themselves. The act of pulling an item is speech, so for those denouncing that, I guess you’d call them a bit hypocritical on the subject. People need to remember that free speech does not equal freedom from criticism, nor does it mean freedom from consequences. Free speech does not guarantee one a platform to engage in that speech. We critiqued the work, we engaged in free speech spinning out of that criticism when it was clear we were being ignored, we asked others to engage in free speech through action. That action, for a publisher to exercise their own free speech in whether to support a comic or not.

I also want to remind folks we were the site that rallied creators and some publishers against internet censorship during the SOPA/PIPA fight in 2012. I wonder where so many of those condemning us now were back then when I reached out to build support within the industry against that legislation in an actual fight over government censorship.

As far as the specific ask, you need to leave room for negotiation. “Pulling” was the extreme ask to leave wiggle room for negotiation. I’ve never gone into a negotiation with exactly what I’ve wanted, I’ve always asked for more to leave room to get what I really want. I think that was lost on a lot of folks, but not exactly something you can say publicly.

Prior to initiating the campaign, did Graphic Policy reach out to creators James Robinson or Greg Hinkle for comment on their portrayal of transgender characters in the comic?

We reached out to numerous stake holders and heard no response in the 36 hours before the action launched. In fact I reached out to other individuals in the industry to get their opinion and was advised to not go forth. We all agreed “censorship” would be hidden behind, and myself and the site would lose face.

In the end, the action wouldn’t have happened if we received a response back that folks were looking into it, even if we had to wait until after Image Expo for an official response. There was no evidence we were heard at all initially or taken seriously.

Quite a few have said that people were busy with SDCC and Image Expo so didn’t notice, but I call BS on that. Look at the number of articles and the chatter over a certain creator taking four tables at a convention within 24 hours. The discussion on Twitter was twice that about the table (which I’m not defending) versus what we brought up. The Outhousers said that their story about the table received 20 times the hits. Let that sink in as far as priorities.

You indicate that you attempted to reach “numerous stakeholders” with no response in the 36 hours before initiating the Twitter campaign. To clarify, did Graphic Policy attempt to communicate specifically with either Robinson or Hinkle on this issue prior to initiating the Twitter campaign?

Everyone was made aware in many ways well before the action launched through various methods. We used numerous channels and contacts we had access to raise awareness of the issue.

When Graphic Policy initiated the Twitter campaign, what was your perception of writer James Robinson’s attitudes towards the transgender community? For example, at the time, did you perceive that the negative portrayal of the transgender community was a reflection of the writer’s beliefs or ignorance about the transgender community, or a non-intended-but-hurtful story gimmick? Did Graphic Policy give any consideration to Robinson’s positive portrayal of LGBT characters in past comics, such as the gay character Mikal Tomas in the DC Comics series Starman?

I was well aware of his portrayal. I read Earth 2 and knew of his work on Starman. I do my research before writing and especially launching an action. But those were gay characters, not transgender. While he was great on those, he messed up here. Just because someone is good as far as the L and the G does not mean they’re good with the B and the T. That’s not a dig at Robinson specifically, that’s society as a whole. Within the LGBTQ+ community there’s issues, so being good on one thing doesn’t give one a pass.

Did I think Robinson insulted folks on purpose? No, it was pretty clear he was putting his character in a situation he thought would enhance that character’s situation. The transgender characters were a prop in this instance, which was part of the issue. He himself said in his apology he “inadvertently hurt and demeaned a community that the real non-fictionalized version of myself truly respects and admires.”

James Robinson has issued an apology via GLAAD regarding the portrayal of the transgender characters in the comic, which Graphic Policy has posted with the comment: “The above does seem sincere, and hopefully this is a learning lesson for all.” What lesson do you feel has been learned from the response to the publication of Airboy #2 and the subsequent apology?

I think that the writer will certainly change the way he works on his stories in the future. I also think a lot of people were educated about transgender issues who haven’t really thought about it before. Those who do care about those issues also now know who their friends are and who aren’t.

This is another great example of the comics community reading something, disagreeing with it, and exercising their power to speak out about it. Even as the minority, we can be heard and move the discussion. We as a community have a long way to go though. Look at how many people spoke out about a creator taking tables at a convention versus this.

Based on your experiences with the Twitter campaign, do you have any advice for comics fans or communities that might want to express their frustrations about perceived unfair gender or social issues in the comics medium?

Yeah, the advice is simple. Support creators and publishers that support you. We’re in a golden age of comics where there’s something for everyone. The second piece of advice is speak out. Frederic Douglass said “Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.” We knew what we did wasn’t going to be popular, but it was right, and doing what’s right is always the way to go especially if you want progress.