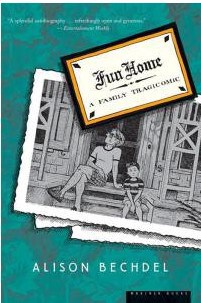

Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home

For a little over three decades Alison Bechdel has been gradually building a reputation as one of the most important talents in sequential storytelling. Beginning with her comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For, she has been a creator of insightful, trailblazing work. Dykes was originally serialized in the feminist Womannews before being syndicated in alternative papers around the country. As her readership grew, the strips were collected in a series of books. At first, Bechdel simply made new installments without any concern for tying them together. Eventually, though, she began employing recurring characters and ongoing storylines. She also used humor to investigate a wide range of social issues relevant to both lesbian culture in particular and the boarder concerns of women in general. Most famously, her strip “The Rule introduced the Bechdel Test, which has become a staple of discussions about representations of women across all media (it was originally used in reference to movies). Dykes made her a prominent voice for her generation, and yet she was only beginning to tap her potential audience.

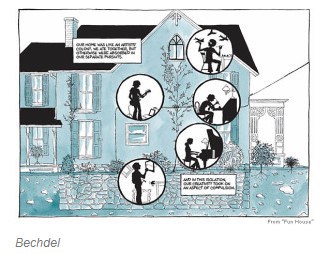

In 2006, Bechdel published Fun Home, a graphic novel memoir. Bechdel had previously experimented with some narrative forms longer than a comic strip, but this was her first full-length book. No matter how complicated its creation may have been (Bechdel’s follow-up Are You My Mother? details just how difficult writing Fun Home was), the final project flows effortlessly. Easily juggling chronology and tone, Bechdel tells the story of her childhood and college years. The thread running throughout is Bechdel’s relationship with her father, Bruce, a closeted homosexual who dies in a presumed suicide.

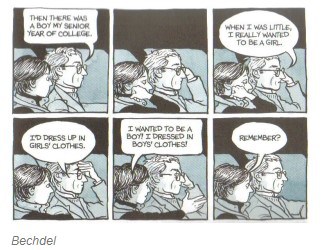

This is sensitive material and Bechdel handles it with the proper amount of tenderness and blunt honesty. Bruce is not an easily likable figure, often cold and distant. He takes more pride in his elaborately renovated home than he does in nurturing his children. (Are You My Mother? interprets a letter from Bruce to his wife, Helen, as a request that she have an abortion). He is most engaged with his daughter when they are in the safe territory of literature. He is continually advising her on which books to read next and what her thoughts on them should be. Whenever Bechdel tries to express her own voice, she finds it lacking her father’s approval. Even a simple decision such as not wanting to wear a barrette in her hair is a source of consternation. Eventually, when Bechdel’s coming out at college forces her father into making some sort of heartfelt response, the letter he writes her is full of confusing statements. “Taking sides is rather heroic, and I am not a hero. What is really worth it? At this moment, Bechdel had no inkling of her father’s preferences, though a phone call soon afterwards with her mother would shine light on that hidden secret.

By telling her story in a non-linear manner, though, Bechdel has been able to share this information with the reader early on, drawing a contrast between what the child knew and what was really happening. Her father was not asexual, often having flings with men, some of whom were underaged. On one occasion, he was caught “supplying an alcohol beverage to a minor and is only able to keep his job teaching high school English due to a lenient judicial ruling (he is sentenced to therapy). Much of his behavior is reckless not only to his family (Bechdel has two brothers) but himself as well. In one touching passage, Bechdel wonders if her father had not died in 1980, how long he might have lasted in the era of AIDS.

In the end, Bruce is a man confined by circumstances which were not of his choosing. He and Helen had planned to travel through Europe, but Helen’s pregnancy complicated matters. Then, Bruce’s father died and he returned to his hometown to help his mother run the family funeral parlor (the Fun Home of the title). Saddled with children, a wife and a constricting life in a small Pennsylvania town, Bruce does not have many opportunities to “make a stand even if he had ever wanted to do so. Through such a lens, Bechdel is able to sympathize with her father without ever excusing his more thoughtless actions.

Naturally, Bruce is only one half of a marriage, the other being his wife Helen. While the core of the book is the Bruce/Alison dynamic, the author does not sideline her mother. Helen is also someone who has seen her life take quite a different turn than she intended. She could have been an actress trying to make her way in New York, but instead is stuck doing community theater in a small town. Bechdel focuses on a summer production of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest wherein Helen played Lady Bracknell. Bechdel uses the play, along with Wilde’s own tragic story, to investigate her parents’ frustrated lives, plus her own future sexual awareness. Through passages such as this, Helen appears as more than a sympathetic victim, but a fully rounded person with virtues and faults all her own. (As the title suggests, Are You My Mother? would dig deeper into the uneasy relationship between mother and daughter).

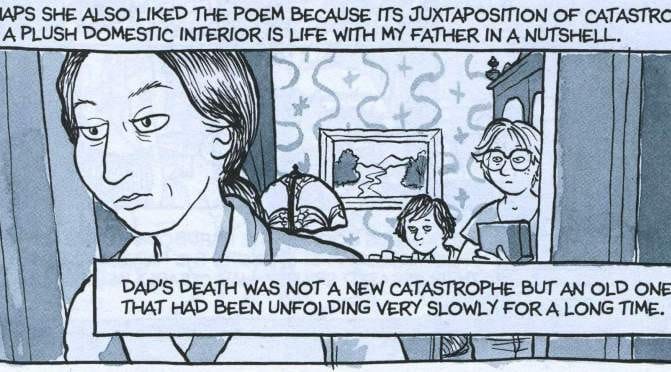

Fun Home is full of telling character moments, and insightful literary allusions, which run the gamut from Greek myth to Wilde to James Joyce, and hence, back to Greek myth again. (If you ever felt bad about not finishing Ulysses, Bechdel did not do much better herself). All of this complicated emotional territory is clearly conveyed by Bechdel’s art. Her origins as a cartoonist can be seen in the pages, yet she builds on them to create something more sophisticated than repeating a three-panel layout ad infinitum. The action flows smoothly without the reader ever being confused by the place or time. She is particularly good at conveying the feeling of a character through a gesture or expression. This book contains many memorable images, such as the child Alison and her dad silhouetted against a setting sun.

In addition to drawings, Bechdel splices in excerpts from family letters or works of literature. In one striking case, she reproduces photographs of her and Bruce when they were each in their early twenties. Each picture shows its subject smiling and carefree. Bechdel wonders if her father’s, taken on his fraternity house roof, was snapped by a lover in the same way the one of her was. On the same page, she inserts a photo of her father in drag from the same period. The lack of context for the image brings home even more the sense of loss not only the person of her father, but the secrets which he was unwilling (unable?) to share. In more ways than one, he took his self away from his children.

Fun Home is a compelling, insightful, outstanding accomplishment and was treated as such upon its release. And not merely within the comics community, where Bechdel was nominated for multiple Eisners, winning one for Best Reality-Based Work. Rave reviews poured in from the literary presses, it was nominated for the National Book Award, and spent a brief moment on the New York Times Non-Fiction bestsellers list. Then two years ago it was adapted into an Off-Broadway musical which earned praise and awards, got transferred to Broadway where it won more praise and trophies including Tony Awards for Best Musical, writing (both story and music) and acting. Bechdel’s audience grew even larger.

This past weekend, I finally saw Fun Home and am happy to report that it does its source material complete justice. A powerful, lively, masterfully acted production, it is entirely worthy of all its accolades. Seeing it also made me think about how this year’s two high-culture honors were both presented to projects with comic connections. The other is Birdman’s Oscar triumph in February. However, whatever Birdman had to say about superheroes, it was not positive. In the movie, they are blamed for a decay in America’s cultural merit, and I suspect many an Academy voter cast their ballot with that in mind. That film had its strengths, but in this aspect it was a cliché view of an industry populated by violence-obsessed men.

The success of Fun Home offers up something else: an example of the type of varied, character-driven projects which we increasingly see more of these days. Is diversity in comics ideal? Of course not. Yet, there are plenty of options for someone who could care less about superheroes punching each other across 22 pages. The industry has matured, and perhaps through creators like Bechdel, so can its image among the general population.

The success of Fun Home offers up something else: an example of the type of varied, character-driven projects which we increasingly see more of these days. Is diversity in comics ideal? Of course not. Yet, there are plenty of options for someone who could care less about superheroes punching each other across 22 pages. The industry has matured, and perhaps through creators like Bechdel, so can its image among the general population.