Etrigan ’92: The Demon Ran for President (It’s True!)

As Iowa’s citizens caucus today to vote for various presidential candidates, Nothing But Comics looks back at the 1992 U.S. presidential bid of Etrigan the Demon in the pages of DC Comics’ The Demon series. In the four-issue story arc “Political Asylum” (The Demon #26-29), writer Dwayne McDuffie, penciller Val Semeiks, inker Bob Smith, and colorist Robbie Busch satirize American politics. Although the creative team pokes fun at the Republican Party’s 1992 presidential primary campaign, the troubling issues lampooned in the story remain relevant to modern politics.

For some context, in 1992, incumbent president George H. W. Bush faced a strong intra-party challenge from Republican conservatives upset with Bush for breaking his 1988 campaign pledge not to raise taxes; these conservatives also desired a more socially conservative policy agenda. Bush prevailed against this challenge led by presidential candidate Pat Buchanan, an articulate conservative pundit and former advisor to three Republican presidents, but the challenge forced Bush to move further right on social issues and culminated in Buchanan giving a controversial keynote speech at the Republican Convention.

Adding to the party’s woes, divisive Republican politician and former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan David Duke also challenged Bush in the primaries. However, Duke received more media attention than votes; he won less than one percent of the votes and no delegates.

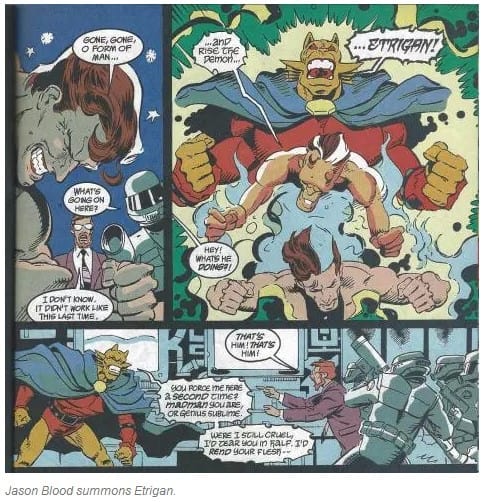

The Demon creative team spoofs this political turmoil, with frustrated conservatives recruiting the vile Etrigan to challenge Bush for the Republican nomination. Comics fans likely know the origin of horned antihero The Demon: the wizard Merlin summons Etrigan (a demon with the odd quirk of speaking in rhyme) from Hell and uses the demon to defend Camelot; when this effort fails, Merlin magically bonds Etrigan to the human Jason Blood, making Blood immortal and giving him the ability to summon/change into Etrigan.

An occult adventurer in modern times, Blood transforms into Etrigan to fight supernatural menaces as “The Demon,” although Etrigan’s demonic nature makes him an untrustworthy ally with sometimes sinister intentions.

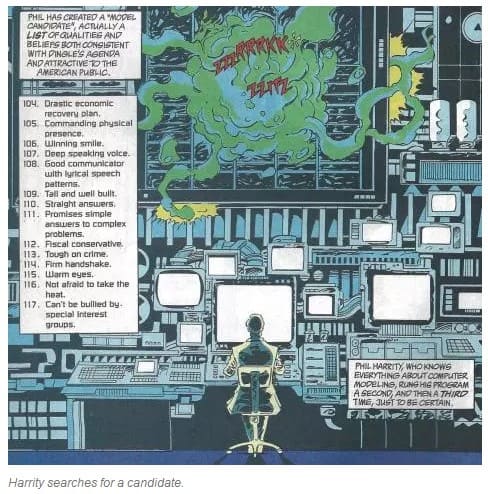

As “Political Asylum” begins, Blood and Etrigan have come to terms, with the demon promising to behave heroically when let loose by Blood. Blood is starting a new chapter of his life, unaware that the obese tycoon Darrin W. Dingle III has summoned prominent pollster Phil Harrity to his mansion. Dingle despises the New Deal legacy of Franklin D. Roosevelt and misses the good old days of Calvin Coolidge; Bush and Buchanan are both too liberal for his tastes. Dingle has built a well-funded organization to take the White House, and hires Harrity to find a suitable candidate to challenge Bush.

Harrity runs a computer modeling program – which lists the ideal candidate qualities desired by both voters and Dingle, qualities that Etrigan humorously possesses – three times, unaware that thrice listing the qualities of a supernatural being serves as a magical invocation. Etrigan appears in Dingle’s mansion, and after some initial violent confusion from both parties, Dingle offers to fund Etrigan’s campaign for president; Etrigan accepts the offer because he secretly wants to use the military might and nuclear arsenal of the United States to conquer both Heaven and Hell.

While the comic’s creative team found satirical inspiration from Buchanan’s right-wing insurgency, note that Etrigan’s campaign, unlike Buchanan’s, is not driven by personal ideological conviction or populist dissatisfaction with the status quo. Rather, Etrigan’s campaign is the vision of a single affluent man with the resources to fund it. McDuffie not only ridicules stereotypical conservatism, but critiques the undue influence of wealthy donors like Dingle on American elections.

McDuffie wrote “Political Asylum” eighteen years before the U. S. Supreme Court decided in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission that the government could not restrict the First Amendment rights of corporations and other groups to spend money on political campaigns. The decision allowed the proliferation of “super PAC” political action committees that can receive unlimited campaign donations from corporations, unions, and individuals, with little regulation from the Federal Election Commission. Although super PACs are required to be independent and uncoordinated with a candidate’s campaign, evidence suggests that this is often not the case.

As a rich conservative, Dingle would likely approve of super PACs. In 2012, approximately 67% of super PAC spending in federal elections supported conservative campaigns, totaling $407 million; approximately half of all federal super PAC expenditures ($303 million) were made by super PACs that did not provide full disclosure of its donors. That year, just 61 wealthy super PAC donors, each contributing an average of $4.7 million, matched the presidential campaign contributions of 1.4 million small donors, and about 60% of all super PAC donations came from 132 donors giving $1 million or more.

In 2012, there were 1,310 federal super PACs; in 2016, there are currently 2,180 super PACs. McDuffie’s concerns about the influence rich donors have on elections are more relevant than ever.

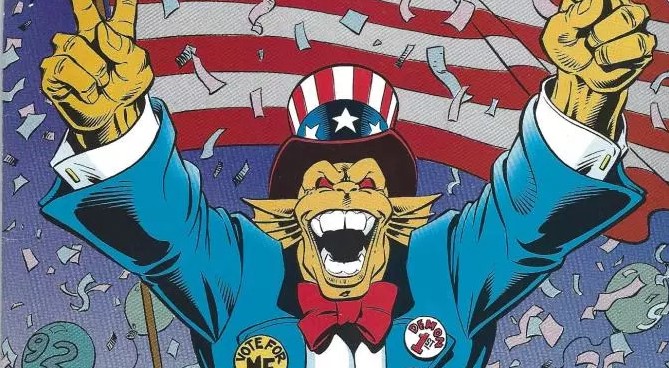

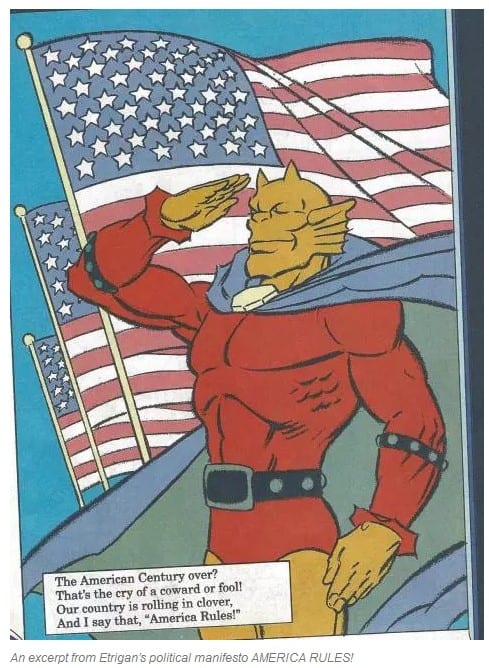

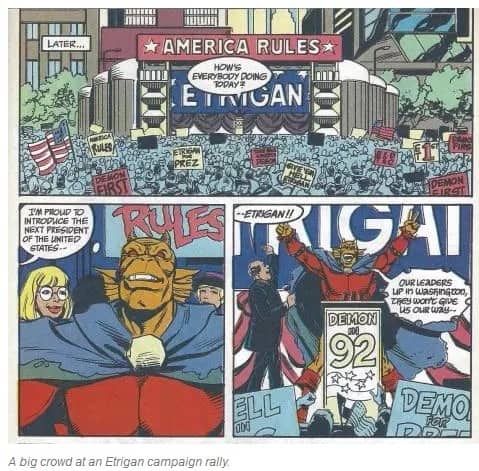

Funded by Dingle, Etrigan wages an unconventional campaign. His political manifesto America Rules! – written in rhyming verse that promises jobs and a strong military – becomes a national bestseller. He feigns a religious conversion to win support from Christian fundamentalists. He has harsh (but rhyming) words for his opponents. He sets fire to journalists that ask tough questions. He physically wrestles Buchanan and Duke to the ground during a debate.

And the people love him for it! Etrigan starts winning state primaries, and his campaign rallies draw huge crowds.

McDuffie satirizes voters’ fascination with political spectacle, suggesting that citizens are more interested in novelty, personality, and entertainment than serious issues; in his story, many voters give a demon from Hell their unconsidered support. In 1992 – an election year in which a sitting president was being challenged by a pundit and a former Klansman, Democratic presidential candidate Bill Clinton played a saxophone on a late-night talk show, and folksy billionaire Ross Perot was funding his independent run for the presidency – the suggestion seemed evident. In 2016, when a controversial billionaire political outsider is a plausible contender for his party’s nomination, McDuffie’s concerns remain justified.

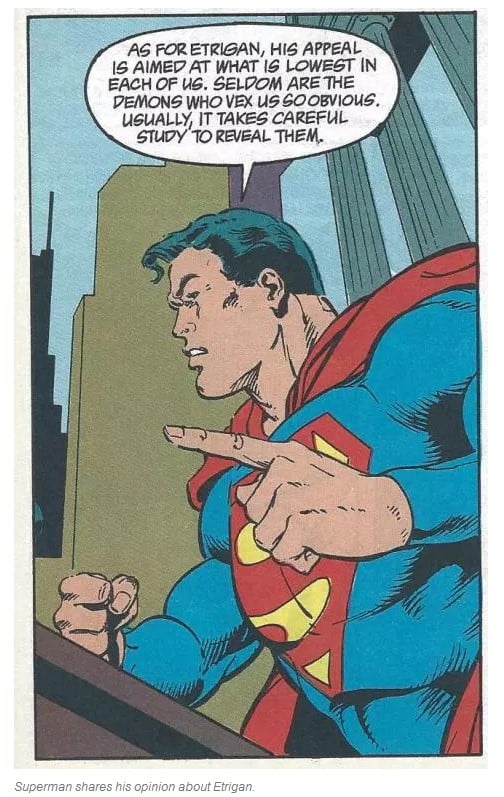

However, McDuffie offers a counterpoint to this cynical view. Iconic superhero Superman appears in the story, initially to stop Etrigan from killing a religious fanatic that attempted to assassinate the demon. Although the two characters briefly come to blows, the most interesting contest is between their two viewpoints – are the American people too good and noble to fall for Etrigan’s base politics, as Superman believes, or is Etrigan’s contempt for democracy warranted?

Superman is reluctant to get involved; his ethics prevent him from meddling in politics. But as Etrigan’s campaign gains support – in part because of false campaign rumors that Etrigan plans to pick Superman as his running mate – Superman leaves his comfort zone and holds a press conference to set the record straight about Etrigan and challenge Americans to be their best. As he states at his press conference: “I can save you from supercriminals… sometimes I can save you from natural disasters. What I cannot do is save you from yourselves.”

No villains are punched, and no one is rescued, but it is arguably Superman’s finest, most heroic moment.

Of course, despite Etrigan’s popularity, there is a big constitutional question to address: as a demon, is he a natural-born citizen of the United States? Given the current questions regarding Senator Ted Cruz’s eligibility to run for president amid concerns about his birthplace and citizenship, it is fun to note how Etrigan addressed this issue – yes, he was born in America, “far below” the city of Metropolis. The issue is settled, extinguishing the hope of Etrigan’s opponents that the demon would be ineligible to serve as president.

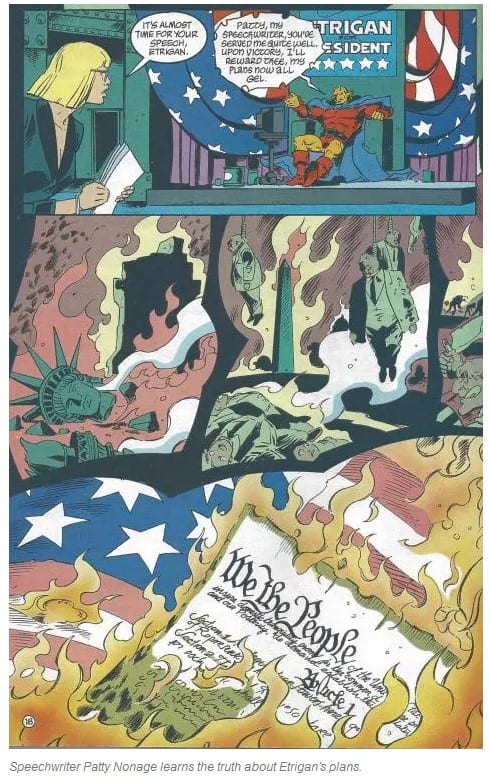

Jason Blood and his friends initially support Etrigan’s campaign, thinking it harmless; they think he has no chance of winning. But at the Republican National Convention, with Bush offering Etrigan the vice presidential spot on the ticket to avoid a floor fight, they realize that Etrigan must be stopped. They are aided by Etrigan’s speechwriter Patty Nonage, who comes to understand the horror of the demon’s ambitions. Together, they thwart Etrigan’s plans, and the demon makes an exit from the political scene.

But the central tension of the story remains unresolved – is Superman right about the political wisdom of the American people, or is Etrigan’s low opinion of voters justified? The Demon isn’t thwarted by the electorate, but by Blood and his allies.

The genius of McDuffie’s story is that it presents readers with an intriguing question that can only be answered at the ballot box: As citizens, are we worthy of Superman’s faith in us, or does Etrigan have a better understanding of our political behavior?