Life During Miracleman’s Golden Age

“I still don’t know what I was waiting for

And my time was running wild . . .”

-David Bowie , “Changes”

In 1982 a young British writer by the name of Alan Moore was tasked with revitalizing the dormant Marvelman property (now known as Miracleman). Over the course of the next several years, Moore would revamp Miracleman for contemporary times, explore the drive for survival and elevate the hero to the status of divinity. Coinciding with his iconic DC work of Swamp Thing, Watchmen and The Killing Joke, Miracleman remains one of Moore’s signature achievements. Moore departed the series on a breathtaking high note, in which Miracleman has become, for all intents and purpose, a god lording over humanity. And unlike Dr. Manhattan’s Enlightenment clockmaker deity, Miracleman had no qualms about employing a heavy hand to guide civilization. Truly, a new age had dawned.

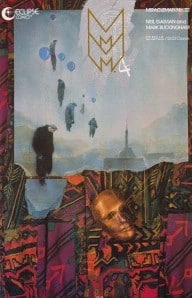

If the Miracleman saga had ended there, it would have been deeply satisfying. Yet, publisher Eclipse preferred to continue the title. Once again, the series was given to an up-and-coming British scribe: Neil Gaiman. Teaming with artist Mark Buckingham, Gaiman began a six issue arc entitled The Golden Age. Despite the daunting task of following in the footsteps of Alan Moore at the height of his powers, Gaiman and Buckingham more than justify the continuation of the series. The Golden Age is a rich, deeply human take on the world. Most importantly it honors what Moore built, while still allowing Gaiman’s own voice to shine.

For The Golden Age, Gaiman shifts the focus away from Miracleman himself. Instead, he centers his stories on a variety of everyday people trying their best to navigate this brave new world. Some of the narratives directly engage Miracleman, such as #17’s “A Prayer and Hope” about a group of pilgrims seeking a wish-granting audience with the deity. Others, for example #21’s “Spy Story”, possess only a glancing connection to the larger canvas. What unites them all, though, is Gaiman’s abiding empathy for the complexities of human nature. Instead of nudging humanity to some higher plain, Miracleman’s interventions have only thrown universal conditions into sharper relief.

All of The Golden Age’s protagonists are searchers, hoping to fulfill some empty space within themselves. Despite all the wonders of the modern world, these familiar human pains linger still. A father’s pleas to save the life of his comatose daughter fall on deaf ears, while a mother fails to receive emotional comfort from a longed for child. A spy builds mental labyrinths around herself, always falling deeper into confused paranoia than clarity. Men pine for love. Adolescents adopt the poses of monsters, failing to understand that a mass murderer has a resonance beyond chic shock value. As with Gaiman’s Sandman (whose own initial stand-alone tales debuted around the same time), these people may exist in extraordinary situations, yet, they remain as relatable as our closest friends.

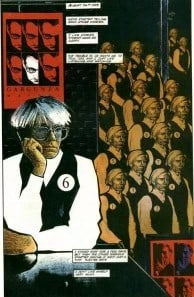

The most fantastic of these circumstances belongs to Andek in #19’s “Notes from the Underground.” As part of his reordering of the world, Moore depicted the alien Qys as living in the underworld of Miracleman’s new Olympus. Qys is experimenting with resurrection of the dead, including celebrities like Andy Warhol (18 of them in fact). Gaiman takes this throwaway line and crafts a whole issue around it. Andek is Andy Warhol #6 and Qys has a special task for him. Qys has resurrected Miracleman’s former nemesis Dr. Emil Gargunza. Gargunza was a genius, personally responsible for splicing the alien DNA into Michael Moran which allowed Mircleman to be born. However, he was also deeply unbalanced, sadistic and obsessed with immortality. Still, Qys wishes to find some way to nurture Gargunza’s mind for good, in order not to waste all that potential brilliance.

Andek and Gargunza form an unease bond (or so it seems), as Andek visits the scientist each day. The Warhols are still hard at work at their art, silk-screening Miracleman themed t-shirts in their distinctive Pop Art manner. Gaiman takes Moore’s concept of Warhol himself becoming a product of mechanical reproduction and really runs with it. The conversations between artist and scientist touch on questions of religion and the existence of a soul. For Andek they are deeply personal dialogues or as personal as the sixth in the series of eighteen might be. Andek wonders which of the Warhols hold their essence. Is it the first? Is it divided equally amidst them all? Or are they all simply empty vessels? Gaiman handles all these exchanges quite well, the conversations never feeling belabored or pedantic. Andek could have been a walking symbol; instead he is a fully alive character, as relatable as any other. His sense of betrayal at the issue’s ending is quite affecting.

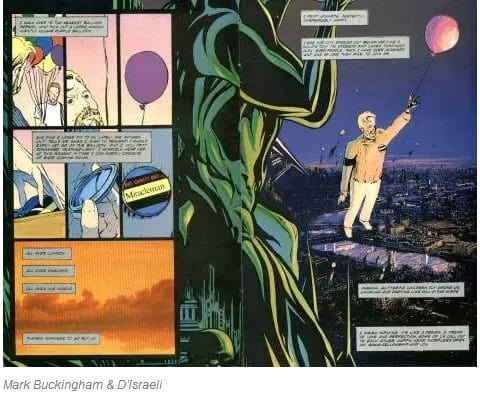

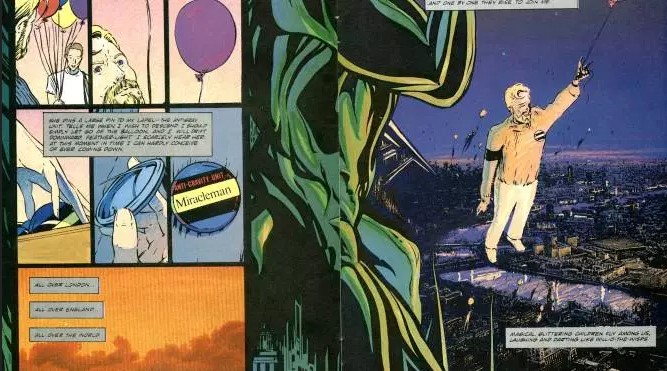

After a strong start from Gary Leach and Alan Davis, the art for Moore’s run could be a bit uneven. Mark Buckingham corrects this trend by proving himself an apt fit for Gaiman’s tales. What is most impressive about his work is how he varies the style according to the story. Sometimes he employs a fairly naturalistic manner, emphasizing the connection to the everyday. For others, such as “Spy Story” his art grows more abstract, mirroring the mental confusion of the protagonist. At times, he uses caricature, such as the wonderfully rotund aunt from “Screaming.” “Trends”, the tale of Johnny Bates admiring adolescents, uses the same cartoonish style, while twisting it to suit the material. What on the surface resembles a children’s comic strip is actually quite darker. (Then again, what childhood was all peaches and cream anyway?). Throughout all these issues, Buckingham reproduces the sense of wonder which now infuses the modern world. From the grandiose opening pages of #17 to the absurd sight of a resurrected Salvador Dali riding a giraffe, Buckingham’s art depicts that this is indeed an age of marvels. At the same time, he never lets it overshadow the human element.

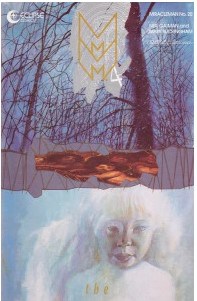

In addition to Buckingham’s interior art, Dave McKean provides covers for each chapter. As in his other collaborations with Gaiman, their sensibilities are perfect match. McKean’s abstract images aptly capture the mood of each story, distilling them to their essence. They are stunning reminders of his fertile talents.

The Golden Age concludes with #22, “Carnival.” Once a year, the world pauses to commemorate the wholesale slaughter Johnny Bates (aka Kid Miracleman) caused while rampaging through London. Eventually Miracleman and his allies stopped Bates, but only after a grotesque (in more ways than one) loss of life. This somber period of remembrance is followed by a celebratory Carnival, the grandest of which, naturally, occurs in London itself. During one year’s festivities, Gaiman gathers together his various characters, weaving a tapestry of humanity. It has been a hard journey for many of them, and yet they have found the strength to persevere.

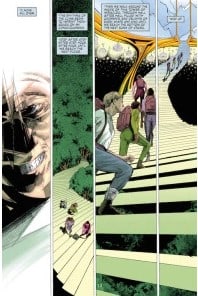

At the day’s end, Miracleman offers the revelers of London a new source of pleasure: balloons which let them float through the sky, as care-free as the birds. (A nod to the classic children’s film The Red Balloon, perhaps?). The final page depicts them drifting against a bright sunset. “I watch the sun setting in slow flame,” one of them muses, “painting the low summer clouds with light . . . purest, most perfect, eternal gold.” Spoken by the father finally accepting the loss of his daughter, these words are a moving statement of hope rising from sorrow. Combined with Buckingham’s beautiful art (he has painted assistance from D’Israeli), they are an indelible conclusion to The Golden Age.

This note of optimism is a striking contrast to Moore’s dark pessimism. By shifting focus away from the god-like Miracleman, Gaiman is able to keep his pulse on the human figures living in the shadow of Olympus. In a sense, nothing has really changed for them. They continue struggling with the same longings and fears that have plagued humanity since the beginning. At the same time, it remains an era of miracles. There may be more changes to come, new ages of silver and even a dark one. However, despite it all, humanity will go on stumbling. In the end, what better advice is there than to “Turn and face the strange”?