In 2010 Drawn and Quarterly released Wilson, the first original graphic novel by the acclaimed writer/artist Daniel Clowes. Despite this distinction, Wilson possesses a serial vibe, often feeling more like a collection of episodic comic strips than a plot driven narrative. This impression is reinforced by Clowes’ decision to vary his art style throughout so that loose cartoons rest opposite pages of more naturalistic detail. What the book lacks in narrative or artistic unity, it gains in thematic cohesion. Wilson displays a biting, if loving, critique of its protagonist as he stumbles through the tribulations of life. The story and the visuals blend to create a very specific ambiance. This mix of comedy and drama was probably what appealed to director Craig Johnson whose previously film, The Skeleton Twins, was focused on a pair of suicidal twins. On paper, Johnson’s sensibility would appear to be a good match for Clowes’. Unfortunately the film Johnson and Clowes, who wrote the screenplay, have produced is an amusing one which fails to live up to its complete potential.

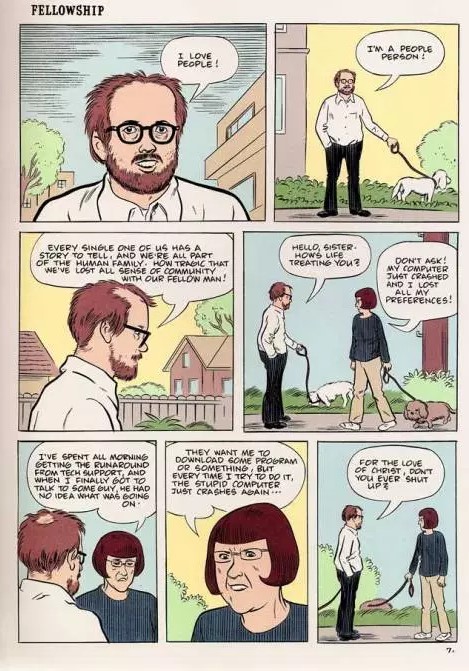

Wilson, the story’s protagonist, is an extreme narcissist. He complains and moans about the state of contemporary culture while remaining blind to his own complacency. He berates others for being glued to their cellphones or computers while reclining on a sofa, appearing to all appearances no more engaged in the “outside world.” He simply drifts through life without much social connection beyond his beloved dog, Pepper. When someone else tries to engage him, Wilson immediately shifts the focus to himself, instantly growing bored by anyone else’s problems, unless he can cite them as further evidence for his own tirades about life. On the other hand, if someone is too busy to pay rapt attention to Wilson’s own moping, clearly they are an insensitive jerk. Such unrelenting negativity could grow rote, yet, in the graphic novel, Clowes deftly avoids it, partially through the tale’s visual variety. Also, the graphic novel, even when events turn dark, maintains an affable tongue and cheek tone. Nothing phases Wilson, which is partially a blessing (keeping things in perspective) and a curse (not being able to learn from anything).

One of the major disappointments of the film is its failure to translate this dynamic to the screen. Many of Wilson’s rants are directly duplicated in the movie yet fail to land with the same bite. At first glance, Woody Harrelson appears to be a good match for Wilson; he is an actor fully capable of delivering Wilson’s snarky commentary on life. However, during the first section of the film, his discourses quickly grow tiresome. His performance tips a little too much to the side of comedy, failing to evoke the melancholy always bubbling near Wilson’s surface. Part of the blame also rests with the director. Johnson never succeeds in replicating the episodic ambiance of the book. Instead the movie’s rhythm feels generic and the satire monotonous. Luckily the film picks up when Johnson and Clowes give Harrelson other actors to play off of.

In one scene, Wilson tries to reconnect with his old friend Olsen, which, predictably, does not go smoothly. David Warshofsky only has the one scene as Olsen yet he leaves an impression by displaying a great sense of comic timing. Similar one-off sequences with Lauren Weedman and Margo (Beloved Character Actress) Martindale also benefit from the talent involved. These could have been disposable cameos whose main purpose was to move the plot forward, but are actually among the film’s funniest and most memorable moments.

The plot of Wilson, as in the graphic novel, centers on Wilson’s actions after the death of his father. He goes in search of his ex (Laura Dern) who left him sixteen years earlier. Finding her leads to other revelations about the fallout from their relationship. Dern’s Pippi is the most complicated character in the movie and, as such, Dern delivers the film’s strongest performance. Pippi has a troubled history of substance abuse, along with hints of having been physically abused by her father. Her relationship with her sister Polly is, on a good day, strained. At times Dern’s Pippi appears brittle, about to crack under the weight of the past. At others, though, she is able to marshal her resources. Her flaws allow to see through Wilson’s defenses while she possesses what he lacks: self-reflection. Unlike her ex, she has the strength to see through her own bullshit.

As engaging as Pippi is in the movie, she does reflect the adaptation’s most confounding element: significant character revisions. In both the book and the film, there is a running joke about Wilson imagining the worst of Pippi’s life since they separated. He believes her to be a drug addict, selling her body on the street, “some bug-eyed freak, some desiccated corpse . . .” In the book, an increasingly exasperated Pippi insists that she was never a prostitute or a drug-addict. It becomes another example of how Wilson’s self-satisfied vision of life supersedes any reality about him. In the film, though, Pippi’s battles with addiction is a real thing; the screenplay never confirms that she was a prostitute but Pippi never denies it with the force she does in the book. Why Clowes thought he needed to drag this character deeper into the mud and by extension, confirm Wilson’s perspective is a bit baffling. Surely Pippi could have been an equally complex character by simply enduring the struggles of the average working class American? It is doubly striking considering how Pippi’s own expressions of emotional emptiness are eliminated for the movie.

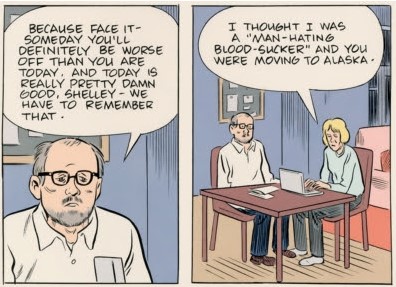

At the same time, Clowes’ screenplay softens Wilson’s character. In the book, Wilson is a viscous ego-maniac, happy to curse out any bystander over the pettiest slight. In the film, he is more of a clown. Many of his most insulting comments are dropped from the movie. A girlfriend’s rebuke “I thought I was a man-hating bloodsucker’ and you were moving to Alaska” is edited to “I thought you were moving to Portland.” Most drastically Clowes drops the final the page of the book which (no spoilers) was the perfect thematic and emotional closing note to the piece. Now the movie ends on a more uplifting note, which allows the possibility that maybe Wilson has learned something about life after all. The flip side of this is that Wilson’s moments of grief in the film feel less sincere than in the book. Taking away his anger, also deprives him of his sorrow. Maybe all he needed after all was a supportive woman to teach him yoga? These matters are not helped by the casting of Dern and Judy Greer in key female roles. While they are both talented actresses, they are both much closer to Hollywood’s traditional expectations for female appearance that the characters Clowes drew in the book.

Compromises are often made when adapting a work from one medium to another; there are very good reasons why the list of “outstanding book & outstanding movie” runs so short. Still, it is disappointing that Clowes believed that so many concessions were needed for Wilson. By discarding the bite, he also discards the soul. This coupled with Johnson’s bland direction leaves the film a bit adrift. It is by no means an utter failure, as it contains some good character work and a few hilarious moments. However, in the end, it never achieves its true potential.