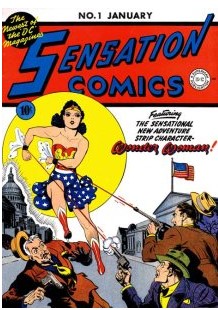

Wonder Woman was not the first superheroine. She had such precursors as Sheena Queen of the Jungle, Miss Fury and Amazona, the Mighty Woman. Female protagonists in the pulps and comic books might have been a very small minority, but they did exist prior to Wonder Woman’s debut in All-Star Comics #8, 1941. Still, there was something different about her, just as there had been that distinctive flair to the Bat-Man, lifting him above the ranks of other late 30s masked vigilantes. Wonder Woman quickly found success, headlining her own anthology series Sensation Comics, which also featured her on every cover (a feat not equaled by Batman during his inaugural year of Detective Comics appearances). In addition, she was given her own quarterly solo title. Fans voted her onto the roster of the Justice Society of America, even if writer Gardner Fox proceeded to minimalize her role in the team to nearly non-existent. As with all social progress, it was a bit of two steps forward, one step back. Regardless, it is fitting to speak of Wonder Woman as belonging, quite consciously, to the cause of cultural and political change.

Wonder Woman was not the first superheroine. She had such precursors as Sheena Queen of the Jungle, Miss Fury and Amazona, the Mighty Woman. Female protagonists in the pulps and comic books might have been a very small minority, but they did exist prior to Wonder Woman’s debut in All-Star Comics #8, 1941. Still, there was something different about her, just as there had been that distinctive flair to the Bat-Man, lifting him above the ranks of other late 30s masked vigilantes. Wonder Woman quickly found success, headlining her own anthology series Sensation Comics, which also featured her on every cover (a feat not equaled by Batman during his inaugural year of Detective Comics appearances). In addition, she was given her own quarterly solo title. Fans voted her onto the roster of the Justice Society of America, even if writer Gardner Fox proceeded to minimalize her role in the team to nearly non-existent. As with all social progress, it was a bit of two steps forward, one step back. Regardless, it is fitting to speak of Wonder Woman as belonging, quite consciously, to the cause of cultural and political change.

In her new book, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, writer Jill Lepore re-examines the biography of William Moulton Marston, who co-created the character with artist Harry G. Peter; Lepore pays particular attention to how his experience overlapped with his involvement with Wonder Woman. Her fascinating book ends up tracking multiple threads involving the history of 20th Century feminism, Marston’s complicated personality and Wonder Woman’s birth and earliest adventures. Lepore ties all these motifs together into a convincing argument that Wonder Woman was a direct product of the progressive philosophies of early 20th Century America.

Born in 1893, Marston came of age at the height of the Suffragist Movement, which contributed a new word to 1910s vernacular: feminism. Lepore draws a sharp distinction between 19th Century Suffragists who felt that women were inherently different than men (more nurturing, less passionate), and these newer feminist thinkers who argued that men and women were essentially the same. They had identical emotional needs (professionally & privately), and therefore should be treated as such. Women did not possess any type of moral superiority, but neither did society’s centuries-old patriarchy. Matriarchy was not the answer, true egalitarianism was. The previous generation was content to win the vote then return to their domestic spheres of child-rearing and home-making. The current generation of activists, which included Marston’s young wife Sadie Holloway, held much different expectations.

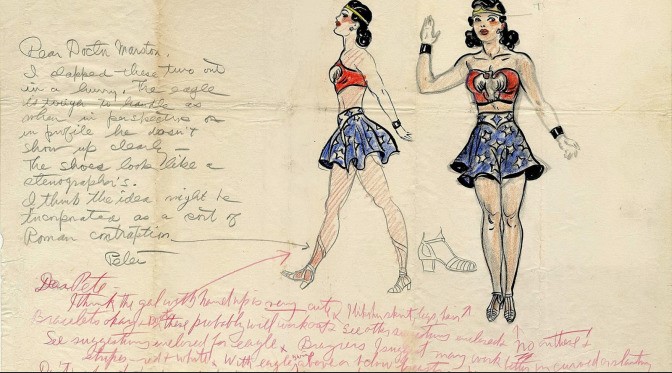

This was more or less the track Marston took when he pitched Wonder Woman to DC Comics. Marston was formerly trained as a lawyer and psychologist, while informally trained in other fields. One of those self-taught trades was writing, though his previous attempts at silent film scripts and prose novels, as well as non-fiction treatises, had not really gotten him anywhere. His career was actually a tangled string of failures. In 1929, he had begun a brief stint in Hollywood as a script “consultant,” and now in the early 40s found himself working at DC using his credentials to keep the social critics at bay. The comics medium had barely come into existence and already the concerned parents, doctors and politicians of the country were trying to derail it. Two years earlier, after a Supreme Court ruling upholding gun regulations, DC editorial ordered that Batman stop using a firearm. Still, publisher Maxwell Charles Gaines was worried about public perception. Marston, always good at eyeing an opening, said the solution was not tinkering with the male heroes, but introducing a female superheroine.

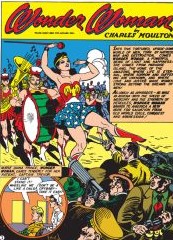

Marston argued that the problem with female heroes in the past, why they never worked in the pulps, was that they “weren’t superior to men.” “The obvious remedy is to create a female character with all the strength of Superman.” Indeed, Marston’s original name for his character was Suprema. (No one ever accused Marston of excessive creativity—he was more of synthesist than an originator). Still, here he did strike on something fresh. The key component of his pitch was the idea that women see themselves as weak because that is how they are portrayed. Traits such as compassion are mistakenly labeled feminine, “sissified” whereas the opposite was true. For Marston, love was key: “the most important ingredient in human happiness . . .” (all quotes this paragraph, Lapore, 187). Having been a young man during one world war (he served but was never stationed overseas) and currently witnessing another, it is understandable that Marston would make his Wonder Woman a disciple of Aphrodite and an antagonist of Ares. (The more I dig into the early years of Wonder Woman, the more problematic Brian Azzarello’s recent run becomes).

Reading the first year of Marston’s Wonder Woman tales (collected together in Wonder Woman Chronicles Volume 1) bares out a lot of these statements. From the beginning, Wonder Woman is an equal to her frequent partner Captain, soon Major, Steve Trevor. They fight side-by-side without showing any discomfort. Indeed, just as Wonder Woman serves as a role model for women, Trevor seems one for men. He never gets upset about being upstaged by a woman; in fact the opposite. When his superiors or the media showers him with praise for a successful mission, he always defers, giving the credit to Wonder Woman. (“I did nothing! It was Wonder Woman!” is a standard refrain of his). She is the true hero, not him. In addition, Wonder Woman is not the only strong woman in these pages. Frequently she calls on her friend Etta Candy and the other female students of Holliday College. One of her earliest adventures (from Sensation Comics #2) ends with Wonder Woman and the ladies of Holliday College taking out an entire nest of German secret agents. The message is clear: every woman might not have the same powers as Wonder Woman, but they can all follow her example to be as good as any man.

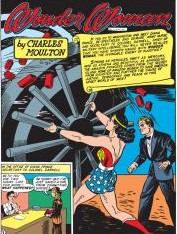

Most of the plots of these stories involve spies, saboteurs and other run-of-the-mill wartime concerns. There are two adversaries, however, which Lepore deservedly singles out in her study. In Sensation Comics #7, Wonder Woman investigates a plot to corner the market on milk in order to drive up the price. Throughout the nation’s capital, children are starving because their mothers cannot afford to feed them. In the end, it is revealed to be a Nazi plot to weaken the next generation of soldiers (since I guess, if you’re at risk of losing one war, best to think of the next one 20 years down the road). Issue #8 though lacks any convenient Nazi scapegoat (though the villain is still European). After a former co-worker nearly shoots herself from despair, women working in a department store demand living wages only to be fired en masse. It is only when the young heiress who owns the store experiences what it is like to be a salesgirl that things change for the better. To understand how progressive these plot points remain today, imagine if the story of the forthcoming Wonder Woman film involved her taking down the current wolves of Wall Street, as well as inspiring all those bikini-clad young women gyrating around them to stand up for themselves.

Life of course is more complicated than pure idealism. Despite all his trumpeting of gender equality, these early stories are full of dated racial stereotyping. (Credit to DC for not sanitizing the reprints). Most of these instances are connected to enemies of a nation at war; for example there are a lot of “voss’s” & “ve’s” in the dialogue. The portrayal of Burmese characters or a hook-nosed talent agent are much more uncomfortable. Some of this is unfortunately typical of the time, but it remains much more prominent than in the first year of Batman stories. Marston came from a long-established, respectable WASP family; he ate Sunday dinner in the family “castle.” He was educated at Harvard. It is easy to imagine that his formative years were rather lacking in diversity.

Marston himself was a rather complicated person. He was a huckster, always looking for the next opportunity to sell something. He tried his hand at many occupations but until hitting on Wonder Woman, more or less failed at all of them. Law, professorships, his claims to inventing the lie detector (another person’s prototype was what eventually entered mass circulation), all of it was pretty much a bust. He conducted “experiments” to prove that redheads excite more easily. In 1937, he held a press conference announcing his belief that a woman would soon be elected president. For years, his household lived off the wages of his wife, while he stormed about making everyone else uncomfortable.

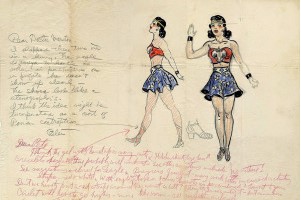

There were plenty of potential sources of awkwardness in the Marston homestead. Lepore digs deeply into Marston’s domestic arrangements revealing that he had, essentially two wives. Olive Byrne was a former student of his, who moved in with him and Holloway after Byrne’s graduation. Holloway was given no say in the matter, though she and Byrne did grow close over the years. Marston had children with both women. Byrne was the child-rearer while Holloway pursued her career. Both women collaborated with Marston (though exactly who edited/wrote what, including the Wonder Woman scripts, is a guessing game). Instead of a wedding band, Byrne wore bracelets which have long been sited at the inspirations for Wonder Woman’s iconic accessories. Byrne was also the daughter of Ethel Byrne who nearly died on a hunger strike for legalized contraception. Ethel’s sister, Byrne’s aunt, was Margaret Sanger, who herself practiced free love. However, as with many a non-traditional domestic arrangement, it is often a thin line between liberation and exploitation.

In the end, my impression of Marston is a man who sincerely believed all of his manifestos on women, feminism and new male/female arrangements. He was not always good at articulating these ideas, let alone following them in his own life. He tended towards the sensational. Yet, at the end of the day, I believe that he wrote what he did for DC because he wanted to show young girls and boys what a woman could be. What we all could be if we stopped fighting and treated each other equally. If we simply loved each other. As with all idealistic mantras, life is much trickier than that. However, that does not make the sentiment any less worthy of aspiration. Perhaps it would not hurt, if these days DC borrowed a little more inspiration from what Marston originally had in mind.