The Birth of Barry Allen and the Silver Age

The first half of the 1950s were not an easy time for superheroes. During the period we now call The Golden Age of Comics, superheroes had been remarkably popular. Superman’s 1938 debut in Action Comics #1 had been a sensation, sparking a boom in four-color crime fighting, which arguably has never been equaled. Just as the relative newness of cinema was fascinating audiences in numbers never to be seen again, comic books were a phenomenon. Then, similar to the movies, tastes changed.

The first half of the 1950s were not an easy time for superheroes. During the period we now call The Golden Age of Comics, superheroes had been remarkably popular. Superman’s 1938 debut in Action Comics #1 had been a sensation, sparking a boom in four-color crime fighting, which arguably has never been equaled. Just as the relative newness of cinema was fascinating audiences in numbers never to be seen again, comic books were a phenomenon. Then, similar to the movies, tastes changed.

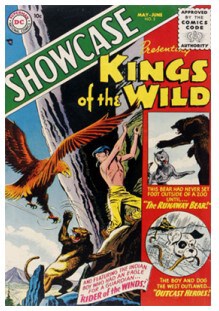

By the end of the 40s, superheroes were on the outs with readers who preferred the rising genres of science fiction and Westerns. Golden Age characters such as the Flash and Green Lantern saw their books canceled, while the Justice Society was evicted from All Star Comics so that it could be rebranded All Star Western. In fact, most of DC’s superhero line ceased to be, except for those titles related to their Trinity of Superman, Batman and Wonder Woman. Even there the series survived by adapting their stories to more favored styles. In 1954, Marvel tried reviving Captain America, though that fizzled out fairly quickly. By 1956, it appeared that costumed crime fighting was a fad that had had its day.

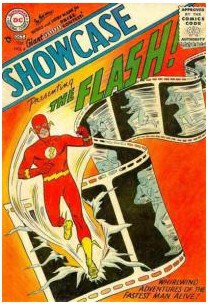

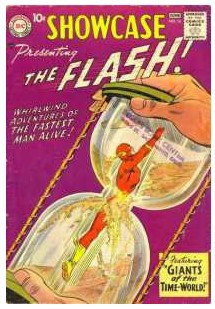

Longtime DC editor Julius Schwartz felt otherwise. He believed that there was reader interest in new superheroes, and decided to use the newly launched anthology series Showcase to try out his theory. The previous issues of Showcase had promised readers tales of firemen, frogmen (as in deep-sea divers) and “the Indian boy who had an eagle for a guardian.” Issue four offered something else: “whirlwind adventures of the fastest man alive.” Schwartz had decided to revisit DC’s dormant Flash property. However, instead of bringing him back as is (what Marvel more or less attempted with Steve Rogers), he tasked writer Robert Kanigher and artist Carmine Infantino with the creation of a new character: new origin, new secret identity, new costume design, new everything. The only thing that remained the same was the name: the Flash. In other words, Kanigher and Infantino were to act as though the Golden Age Flash Jay Garrick had never existed.

The result of this collaboration was published in Showcase #4 as “Mystery of the Human Thunderbolt.” The story introduces police scientist Barry Allen, sitting in his crime lab drinking milk while reading a comic book featuring the fictional exploits of the Jay Garrick Flash. (This is the only acknowledgement that Kanigher gives to Garrick though it would later serve as a seed for Gardner Fox’s iconic tale “Flash of Two Worlds”). After his break, he is at work with his instruments when lightning strikes, toppling a shelf and giving Barry a “bath” in chemicals. This being the 50s, Barry seems more concerned with catching a cab for home than maybe visiting an emergency room. Soon, though, he begins to exhibit strange speed-related abilities. After being able to save his girlfriend Iris West from a stray bullet, Barry decides that he needs to put these powers to a noble use. Glancing again at the Flash comic book, he knows what he must do. And thus, the Flash is reborn.

This new Flash was a success; however, not so much that he reappeared immediately in the next issue. Indeed, he would not return until #8, following the two-part premiere of The Challengers of the Unknown. Then Schwartz held him back again until #13, so that Showcase could run some Lois Lane stories and more Challengers. Finally, in March 1959 Barry Allen had his own series, Flash. In an interesting nod to the past, DC did not launch this new title at #1, but picked up the numbering from where Jay Garrick’s adventures abruptly ended a decade earlier.

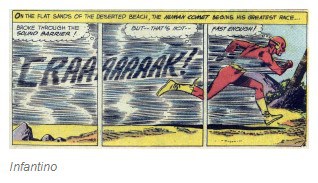

All of these issues contained two Flash stories. In the case of Showcase, writing duties were split between Kanigher and John Broome, while Infantino handled the pencils. Then in Flash Broome wrote all the stories while Infantino continued on art. Both Kanigher and Broome turned in scripts that reflected the popularity of the science-fiction genre. In his second outing, Barry faces a criminal exiled from the future. Other early encounters include a villain from the distant past and invaders from the “Time World.” In the second issue of Flash’s series (Flash #106), Gorilla Grodd makes his debut, in a story not dissimilar from the various monstrous animal films common at the time. There is also a strong scientific component to several of Broome’s stories, where Broome tries to ground outlandish occurrences in factual science. This was during America’s Space Race with the Soviet Union, when grooming a generation of brilliant scientists was very much public concern. Schwartz and his creators were smart. They revived the superhero genre by adapting it to contemporary tastes.

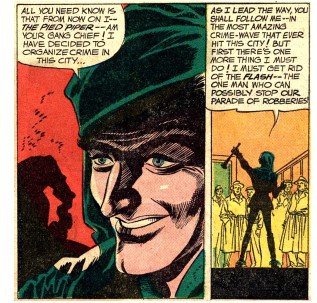

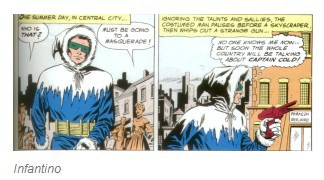

At the same time, they did not shy away from the tropes of superheroes. Besides villains such as Grodd or Katmos (who with only a single appearance to his name is ripe for revival), Broome introduced numerous costumed adversaries for Barry Allen. Broome’s contribution to Barry’s second Showcase outing was “The Coldest Man on Earth,” aka Captain Cold. He was soon followed by such colorful characters as Mr. Element (rechristened Doctor Alchemy in his return appearance; he would later go on to be a Blue Beatle antagonist), The Master of Mirrors (aka Mirror Master) and Pied Piper. These battles with masked criminals are the most enjoyable stories. The Rogues are one of the most important elements of Barry Allen’s legacy, and their appeal is evident from the beginning. Broome makes them engaging antagonists, while Infantino illustrates it all expertly. Soon other familiar faces, such as Trickster and Captain Boomerang, joined the growing ranks of Central City’s costumed criminal class.

If there is one component of these stories that has not dated as well, it is looseness of Barry’s power set. For example, in “The Man Who Broke the Time Barrier,” Barry solves the problem of the stranded outlaw from the distant future by easily speeding through the “time barrier” into the year 3000. In another issue, he is able to carry a man sized gorilla on his back all the way to Africa due to the “enormous strength” granted by his super-speed. At times, it feels as though Kanigher and Broome simple invented for the Flash whatever ability they needed to wrap up the adventure in the required page count. However, in the end, that is only a minor compliant. For the most past, these stories hold up pretty well and are still a lot of fun to read, especially Broome’s. For this article I read the tales collected in DC’s Flash Chronicles Volume 1, and now would like to move on to the next volumes.

Revivals, reboots, legacy heroes and so on are such a common occurrence in comics these days, we sometimes forget how daring Schwartz was back in 1956. Yet, his gamble worked. Gradually, he built up the appearances of the Flash so that by the end of the decade not only was Barry Allen popular enough for his own book, but Green Lantern was given a similar treatment transforming the Golden Age’s Alan Scott into Hal Jordan. A year later, the Justice Society was reformed as the Justice League. And so, as a new decade dawned superheroes were once again firmly entrenched in comic books. The Silver Age of Comics was here. Schwartz’s reboot of the Flash was not only one of the earliest in the medium, but the one with the longest legacy.