William Moulton Marston was never one to shy away from publicity; indeed he reveled in it. In 1937 he held a two hour press conference during which he elaborated on his theories concerning the inevitably of an American matriarchy. He must have sounded convincing as a Los Angeles Times headline claimed “Feminine Rule Declared Fact.” All this hub-bub was to promote the release of his new book Try Living, in which he stated the secret to happiness was doing something you love. According to the Times, he offered up six individuals as exemplars for his theory. Ranking them in order of importance, he held Margaret Sanger as #2, right above the current president, Franklin D. Roosevelt. (For those playing along at home the first was Henry Ford, a reminder that Marston’s egalitarian views sadly did not extend to racial issues). Still, sweeping away the pseudo-psychological language Marston was so fond of, he was not entirely out on a limb on this matter. The changing role of women in society (what used to be called “The Woman Question”) was a serious political topic. Louis Howe, secretary to President Roosevelt, wrote that the election of a female president was a definite possibility at present, not in some distant future. Howe may have crouched his opinion in more cautious statements than Marston’s grand speechifying, but they were both speaking of the same cultural trends. In an era of Sanger and Eleanor Roosevelt, surely women could only expect further improvements in their status?

Despite all this coverage, Try Living failed to leave a mark. In this way, it conformed to the pattern of most of Marston’s endeavors: he could write a fantastic press release, but often stumbled at the actual follow-through. The sole exception to this trend was when he pitched to DC the idea for a female superhero named Wonder Woman. This time the concept not only stuck but was a rousing success. Thus, it was as a comic book scribe that Marston was able to revisit his vision for what a 31st Century world ruled by women might look like.

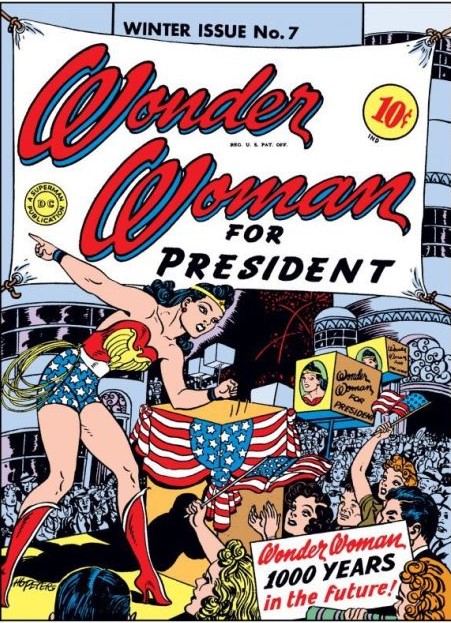

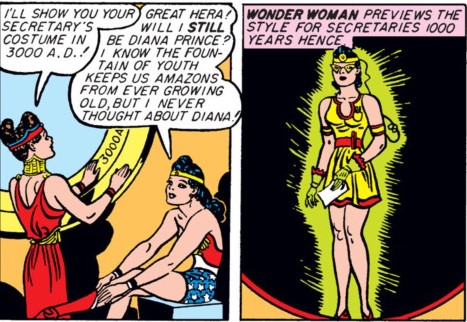

From her inception, Wonder Woman was meant to be a symbol of women’s full potential. Paradise Island, regardless of whether Amazons or goddesses are calling the shots, is very much a matriarchy. Hence one of the reasons, Diana has so much trouble at first grasping how the “Man’s World” operates. Wonder Woman #7 (1943) opens with a light-hearted take on this theme. Diana’s mental radio goes off at 3AM, prompting a groggy Diana to observe “I’m getting the silly Man’s World habit of sleeping all night.” Diana answers the mental radio and her mother Hippolyta’s request to travel home to Paradise Island for the annual Harvest Festival. Luckily it coincides with her Thanksgiving leave from army duties. Diana decides to surprise Hippolyta by arriving in her secretarial uniform, which in turn prompts a discussion of what secretaries will be wearing 1000 years from now. Hippolyta can learn such things by studying the Magic Sphere which predicts future events based on past occurrences. Having admired the alluring, practical garb of the 31st Century woman, Diana laments her non-Amazonian friends will not live to witness such delights. Ah, informs Hippolyta, just look again.

In the near future, Diana stands by her dear friend Etta Candy as Etta weeps at the bedside of her dying mother, Sugar Candy. Etta is distraught that all her studies in science have failed to produce a cure for her mother’s illness. Wonder Woman produces some water from Paradise Island’s Fountain of Youth, which, Etta in turn is able to activate the life giving properties of through, well, more Marston pseudo-science. Soon Sugar’s life is not only revived but her youth restored. Etta wins the highest scientific accolades and all of Wonder Woman’s companions in the Man’s World are able to live to see the year 3000 when women confidently hold the reins of power.

When Arda Moore is elected president of the United States she acts rapidly to change the status quo of politics. She reforms government by ending the practices of political bosses such as Grafton Patronage who is now serving time in prison. Some forward thinking men support President Moore’s reforms, including General Darnell and Colonel Steve Trevor (poor bloke, Steve, over 1000 years of dedicated service and no promotion in the ranks?). As might be expected, though, there are reactionary forces which fear the new standards. There is Senator Heeman, a brusque, cigar-smoking agitator for the Men’s World Party, who demands Moore let free Patronage. It might be easy for present day readers to roll their eyes at the bluntness of Marston’s name choices, yet, what they represent runs deeper. Political change always inspires negative pushback, which often threatens to turn violent, as it does here. Luckily Wonder Woman’s skills and quick thinking save the day.

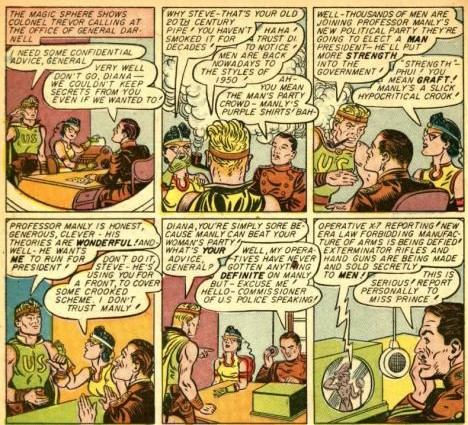

However, there is more upheaval still to come. Hippolyta spins the Sphere ahead a few years to 3004, revealing that the man’s movement has grown beyond a fringe occurrence. Even once reliable Colonel Trevor has been swept up by Professor Manly’s pledge “to put more strength back into government.” Diana counters that such soaring language is empty, nothing but a front for some “crooked scheme” which Manly has planned. Manly is nothing but a hypocrite, a charlatan exploiting the sensibilities of others. Steve is unmoved. He professes Manly as “honest, generous and clever.” Steve has even adopted the Man’s Party fad of returning to the fashions of the 1950s. Oh, and Manly wants Steve to run on the Man’s Party ticket for president. General Darnell has nothing definitive with which to convict Manly, yet he shares Diana’s distrust of the professor and his Purple Shirt followers.

Marston wrote “America’s Wonderland of Tomorrow” in 1943 while the country was still in the midst of World War II. His designation of Manly’s followers as Purple Shirts would instantly have brought to mind Adolf Hitler’s brownshirts and Benito Mussolini’s blackshirts. That Marston would link reactionary patriarchy with European fascism is hardly surprising. It is no coincidence that Wonder Woman’s costume displays the iconography of her adoptative country. She was a product of contemporary events in Europe as much as Steve Rogers was. In Marston’s mind, women’s rights and democracy were inexplicably linked; if women did not have full equality, than democracy could not exist. Wonder Woman could not only break the chains of female oppression but could inspires the fight against broader political tyranny. By overcoming Ares and his Axis puppets she could usher in a new age of Aphrodite. As Hippolyta reminds her daughter “. . . all men are much happier when their strong aggressive natures are controlled by a wise and loving woman.”

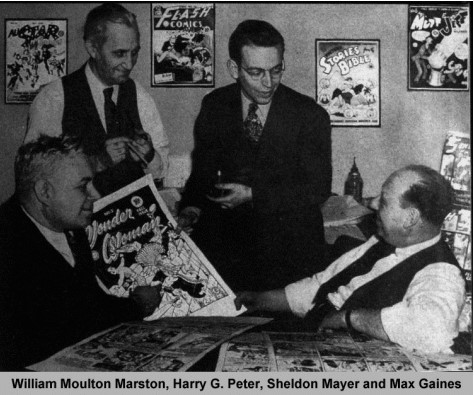

Yet, crisis in the Man’s World often require fists to resolve problems. This contradiction, the symbol of peace often resorting to violence, is one of many within Marston’s work. Wonder Woman is the champion of democracy, while her mother rules over a monarchy with heavy theocratic overtones. In addition, Marston’s privileged background blinded him to matters of racial inequality. When Hippolyta glances forward at 31st Century fashion, why instantly leap to secretaries, instead of the gowns worn by the president? Then there was Marston’s personal life. Marston was married simultaneously to two women, Elizabeth Holloway and Olive Byrne. They all lived in the same house, raising both women’s children as Holloway’s (even Byrne’s children did not learn for years who their birth mother was). This attitude towards family structure was adopted for Marston’s professional work as well. At the very least, Byrne typed Marston’s manuscripts; she may have written parts of them too. Same with Holloway. Both women made contributions to the creation of Wonder Woman. For example, Diana’s iconic bracelets were modeled after a pair Byrne wore in lieu of a wedding ring. Marston was not an easy husband or father with which to live. He suffered fits of rage and despondency. Untangling where shared lives end and exploitation begins is quite tricky. Marston receives sole author credit for his Wonder Woman stories, though, how accurately is impossible to say. It is safe to say, however, they reflect his idealistic belief in a changing society.

The problem with idealistic visions is they never quite come to pass in the same manner in which they are dreamt. One of the most heartbreaking sections of Victor Hugo’s novel Les Miserables (1862) is the one detailing the student activists’ resistance to and death at the hands of French soldiers. This is not simply a result of the inherent tragedy of their demise but also what history teaches of their beliefs. The Friends of the ABC, as they styled themselves, were fighting for the end of monarchy and a return to democracy. Once democracy is restored peace will reign. War was a product of kings who ruthlessly pursued conflict in the name of their own selfish ends. Their lofty social position shielded them and their court from any of the true consequences of combat. A republic would be different. Legislators would never vote to send their own to die in senseless conflicts. Hence, as the students saw it, their deaths that day upon the barricades were worth it, for their sacrifice would help nudge the world a little closer to tranquility.

Hugo lived long enough to see such idealism thrashed by reality. Yet, the appeal of democracy remains. Flawed as it is at times, it is still sounder than the alternative of authoritarianism. The same with Marston’s views on gender. Many of the feminists of Marston’s day were shifting away from the previous generation’s concepts of womanhood. The Suffragists argued that women should have the vote because of their unique perspective as mothers and homemakers. When Louis Howe contemplated a female president he did through reaffirming traditional gender stereotypes. Howe observed that as the nation became more preoccupied with “humanitarian, educational” concerns it would be logical to elect a female president since she would “better understand such questions than men.” Wonder Woman #7’s portrait of the future presents a similar idealized view of feminine influence. Again, though, history says otherwise. It is ironic that Marston chose the 1950s (which was the future for him) as the preferred era of reactionary chauvinists. Times never change as quickly as the activists proclaim they will. Lasting change is incremental, not sweeping. This is one of the reasons Marston’s Wonder Woman remains so striking 75 years later. His stories may not have been the most subtle, yet many of their elements are as boldly radical today as when they were first published.

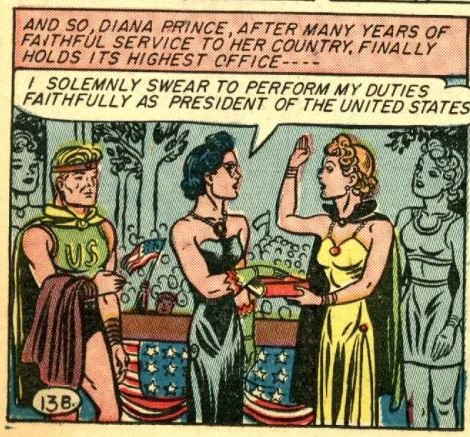

As for the election of 3004, yes, it turns out Diana’s instincts were correct and Manly was exploiting Steve. The election is close and Manly employs deception to rig the results in his favor. Steve might be a dope at times, but, he is an honest one, refusing to destroy the evidence. Wonder Woman intervenes, though she only triumphs through the scientific expertise of Etta Candy. Thus, Diana Prince is sworn in as the next President of the United States.

Marston conceived of Wonder Woman as an inspirational figure who, along with her companions from Holiday College, would demonstrate that women could do anything. They might meet resistance from bitter, reactionary elements, but such obstacles could be overcome through skill and perseverance. The future was theirs to claim, as much as any man’s. The first female president did not arrive in the 40s as some mused, however, there is a very good chance that she will assume office much sooner than the 31st Century. And perhaps, despite all his internal contradictions, Marston’s Wonder Woman played her small part in making such cultural change possible.

Cheers

Background information on William Moulton Marston is drawn from Jill Lapore’s biography The Secret Life of Wonder Woman. It is highly recommended for further reading on Marston’s life in general and the creation of Wonder Woman in particular. All quotes relating to Marston’s 1937 press conference and Louis Howe’s consideration of a female president come from Lapore, pg. 169-173.