This Week’s Finest: The Wicked + the Divine #28

As previously observed, The Wicked + the Divine has always been focused on the subject of youth. However, this has hardly caused the series to remain static—quite the opposite in fact. One of writer Kieron Gillen’s motifs has been how the devil-may-care attitudes of adolescence gradually cede to the responsibilities of adulthood. The initial arcs depicted a Pantheon fully in thrall to their newfound powers; most of the freshly minted divinities were luxuriating in dazzlingly heights (or lows, if you were the Goth type with a preference for moping through poorly lit tube stations). It is true that mortality haunted The Pantheon from nearly the beginning striking down some of its brightest stars. Perhaps this is another reason why the brilliant Tara chapter (#13) struck such a deep chord: here was a portrait of a god buckling under the weight of her mantle. Tara never sought fame and all its trappings; indeed she desired as much anonymity as possible. When she turned to Ananke, The Pantheon’s mentor, for relief,, Tara was brutally rebuffed. In death she became another reminder of the finality which waits even for the divine. In fact, each time a Pantheon member has died, the tone of the narrative has shifted. Lucifer’s demise moved the theme from cheeky world-building concept to heart-wrenching poignancy. Inanna and Tara’s deaths deepened this somber atmosphere. Then Persephone’s killing of Ananke altered the status quo even more drastically. Adult supervision was gone and the children were left to fend for themselves. What would they do now that the only authority was their own? “Whatever we want,” Persephone declares. As the first half of Imperial Phase powerfully draws to a close, the reader is left wondering just how well that anthem is working out for any of them.

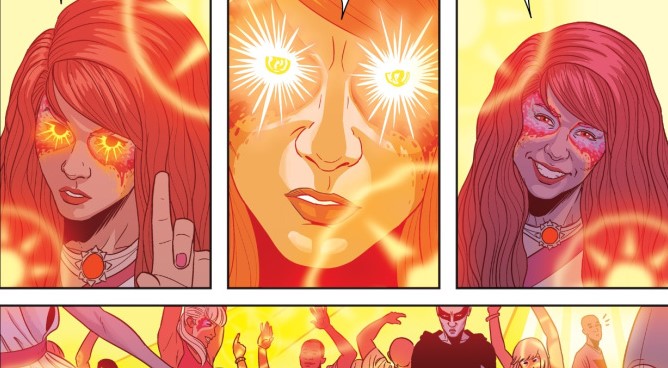

After a brief prologue examining Cassandra’s continuing need for research, the issue settles into a rather hedonistic vibe. This ambiance is established rather succulently by Woden’s proclamation “Godhood on cocaine? Now we’re fucking talking!” Upstairs a trio of goddess are primping themselves in luxe accommodations. The setting is Amaterasu’s Temple, which, fitting for a sun goddess, colorist Matthew Wilson fills with a radiant glow. This is Amaterasu’s party and she will let nothing dampen it. Amaterasu has a peppy, radiating personality. More than any Pantheon member, save Dionysus, artist Jamie McKelvie illustrates how Amaterasu’s charisma spreads to those around her. Patterns of energy swirl and dance about the room, subsuming it in her joy. Wilson’s hazy coloring provides the perfect accent to McKelvie’s imagery. Amaterasu is the type of party girl who refuses to take no for an answer, dragging one and all to another club for another round. Why stop or even slow down when everything is so fabulous? She will embrace you with her warmth, even if first she must threaten disintegrating you in her fire. In a three panel sequence, McKelvie represents the goddess’ shifting tones through her facial expressions, using subtle visual hints to communicate the volatile mixture of youth and raw power which is Amaterasu.

In many ways, Amaterasu has always come off as the least mature of The Pantheon, which extends to her rather wide-eyed pursuit of pleasure. The idea that her choices could cause other harm seems foreign to her. Sakhmet, on the other hand, has always displayed a darker streak. She know she might cause harm; she simply does not care. Where Amaterasu and Dionysus keep the party flowing out of a sense of communal empathy, Sakhmet has no time for false delusions. When Persephone tries to draw Sakhmet into a conversation about human nature (& its discontents), Sakhmet brushes her off with some pat cynicism. “Stop trying to trick emotions out of me,” she chides before moving on to more pressing matters. “How do I look?” To be fair, Sakhmet does look fabulous. Decked out in a tight red dress with a striking golden lion’s head front piece, she easily conveys the graceful, powerful poise of her divine feline attributes. Later in the issue, when she asks who wants to go to bed with her, the sea of hands in response is hardly surprising. Also not surprising is that one raised arm belongs to the beaming Amaterasu.

When we are young, it is easy to be caught up in the moment, believing that we have an obligation to pursue every possibility, exploring each to its furthest extent. There are times when such choices are laudable, even essential, to the growth process. Yet, left unchecked they can wound in unexpected ways. Life, in the end, is not an ad-hoc collection of isolated moments but a string of events building on and, as much as our limited perspective allows, informing each other. More than once in #28, the outside world crashes Amaterasu’s party and each time she brushes it away until finally it snaps back at her. Suddenly what was once lithely sensual is now viciously soaked in blood. McKelvie shines in this sequence, demonstrating a mastery of pacing and atmosphere. He effortlessly transitions from the orgy’s sexual debauchery to a god’s raging bloodlust. Panels grow more cramped, as the tension in the room rises. Whole sections of the page turn black, conveying the brutal speed at which events spiral out of control. Wilson underscores this by subtly shifting from the subdued reddish orange of candlelit passions to the darker more menacing hues of carnage. The reader hardly sees any of the actual outburst, though they feel its full explosive fury. It passes in the blink of an eye. The aftermath, however, is depicted in all its gory detail as a goddess stands at the center of the page, gently dabbing her cheek with a bloody bedsheet.

Youth is temperamental. Youth with the powers of a god is a massacre waiting to happen. The adult is gone and the children are free to do “whatever we want.” Hedonism has its superficial charms and there are times when such pleasures are beneficial as a stress release. However, when completely detached from any groundings, they can be quite harmful. Part of maturing is acknowledging this need for self-examination and admitting the effect our actions have on others. To not learn this lesson results in stagnation. The pressing question before The Pantheon is will they, given their truncated life spans, live long enough to learn greater responsibility. And if not, what are the true costs of ignorance? Gillen and Mckelvie end the issue with an affecting twist which adds another wrinkle to these questions: perhaps the elder generation possessed, along with their mistakes, more wisdom than they were given credit for having? It would not be the first time. Learning from experience does count for something, after all.